Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.

That, more or less, is the short answer to the supposedly incredibly complicated and confusing question of what we humans should eat in order to be maximally healthy. I hate to give away the game right here at the beginning of a long essay, and I confess that I'm tempted to complicate matters in the interest of keeping things going for a few thousand more words. I'll try to resist but will go ahead and add a couple more details to flesh out the advice. Like: A little meat won't kill you, though it's better approached as a side dish than as a main. And you're much better off eating whole fresh foods than processed food products. That's what I mean by the recommendation to eat "food." Once, food was all you could eat, but today there are lots of other edible foodlike substances in the supermarket. These novel products of food science often come in packages festooned with health claims, which brings me to a related rule of thumb: if you're concerned about your health, you should probably avoid food products that make health claims. Why? Because a health claim on a food product is a good indication that it's not really food, and food is what you want to eat.

Uh-oh. Things are suddenly sounding a little more complicated, aren't they? Sorry. But that's how it goes as soon as you try to get to the bottom of the whole vexing question of food and health. Before long, a dense cloud bank of confusion moves in. Sooner or later, everything solid you thought you knew about the links between diet and health gets blown away in the gust of the latest study.

Last winter came the news that a low-fat diet, long believed to protect against breast cancer, may do no such thing — this from the monumental, federally financed Women's Health Initiative, which has also found no link between a low-fat diet and rates of coronary disease. The year before we learned that dietary fiber might not, as we had been confidently told, help prevent colon cancer. Just last fall two prestigious studies on omega-3 fats published at the same time presented us with strikingly different conclusions. While the Institute of Medicine stated that "it is uncertain how much these omega-3s contribute to improving health" (and they might do the opposite if you get them from mercury-contaminated fish), a Harvard study declared that simply by eating a couple of servings of fish each week (or by downing enough fish oil), you could cut your risk of dying from a heart attack by more than a third — a stunningly hopeful piece of news. It's no wonder that omega-3 fatty acids are poised to become the oat bran of 2007, as food scientists micro-encapsulate fish oil and algae oil and blast them into such formerly all-terrestrial foods as bread and tortillas, milk and yogurt and cheese, all of which will soon, you can be sure, sprout fishy new health claims. (Remember the rule?)

By now you're probably registering the cognitive dissonance of the supermarket shopper or science-section reader, as well as some nostalgia for the simplicity and solidity of the first few sentences of this essay. Which I'm still prepared to defend against the shifting winds of nutritional science and food-industry marketing. But before I do that, it might be useful to figure out how we arrived at our present state of nutritional confusion and anxiety.

The story of how the most basic questions about what to eat ever got so complicated reveals a great deal about the institutional imperatives of the food industry, nutritional science and — ahem — journalism, three parties that stand to gain much from widespread confusion surrounding what is, after all, the most elemental question an omnivore confronts. Humans deciding what to eat without expert help — something they have been doing with notable success since coming down out of the trees — is seriously unprofitable if you're a food company, distinctly risky if you're a nutritionist and just plain boring if you're a newspaper editor or journalist. (Or, for that matter, an eater. Who wants to hear, yet again, "Eat more fruits and vegetables"?) And so, like a large gray fog, a great Conspiracy of Confusion has gathered around the simplest questions of nutrition — much to the advantage of everybody involved. Except perhaps the ostensible beneficiary of all this nutritional expertise and advice: us, and our health and happiness as eaters.

FROM FOODS TO NUTRIENTS

It was in the 1980s that food began disappearing from the American supermarket, gradually to be replaced by "nutrients," which are not the same thing. Where once the familiar names of recognizable comestibles — things like eggs or breakfast cereal or cookies — claimed pride of place on the brightly colored packages crowding the aisles, now new terms like "fiber" and "cholesterol" and "saturated fat" rose to large-type prominence. More important than mere foods, the presence or absence of these invisible substances was now generally believed to confer health benefits on their eaters. Foods by comparison were coarse, old-fashioned and decidedly unscientific things — who could say what was in them, really? But nutrients — those chemical compounds and minerals in foods that nutritionists have deemed important to health — gleamed with the promise of scientific certainty; eat more of the right ones, fewer of the wrong, and you would live longer and avoid chronic diseases.

Nutrients themselves had been around, as a concept, since the early 19th century, when the English doctor and chemist William Prout identified what came to be called the "macronutrients": protein, fat and carbohydrates. It was thought that that was pretty much all there was going on in food, until doctors noticed that an adequate supply of the big three did not necessarily keep people nourished. At the end of the 19th century, British doctors were puzzled by the fact that Chinese laborers in the Malay states were dying of a disease called beriberi, which didn't seem to afflict Tamils or native Malays. The mystery was solved when someone pointed out that the Chinese ate "polished," or white, rice, while the others ate rice that hadn't been mechanically milled. A few years later, Casimir Funk, a Polish chemist, discovered the "essential nutrient" in rice husks that protected against beriberi and called it a "vitamine," the first micronutrient. Vitamins brought a kind of glamour to the science of nutrition, and though certain sectors of the population began to eat by its expert lights, it really wasn't until late in the 20th century that nutrients managed to push food aside in the popular imagination of what it means to eat.

No single event marked the shift from eating food to eating nutrients, though in retrospect a little-noticed political dust-up in Washington in 1977 seems to have helped propel American food culture down this dimly lighted path. Responding to an alarming increase in chronic diseases linked to diet — including heart disease, cancer and diabetes — a Senate Select Committee on Nutrition, headed by George McGovern, held hearings on the problem and prepared what by all rights should have been an uncontroversial document called "Dietary Goals for the United States." The committee learned that while rates of coronary heart disease had soared in America since World War II, other cultures that consumed traditional diets based largely on plants had strikingly low rates of chronic disease. Epidemiologists also had observed that in America during the war years, when meat and dairy products were strictly rationed, the rate of heart disease temporarily plummeted.

Naïvely putting two and two together, the committee drafted a straightforward set of dietary guidelines calling on Americans to cut down on red meat and dairy products. Within weeks a firestorm, emanating from the red-meat and dairy industries, engulfed the committee, and Senator McGovern (who had a great many cattle ranchers among his South Dakota constituents) was forced to beat a retreat. The committee's recommendations were hastily rewritten. Plain talk about food — the committee had advised Americans to actually "reduce consumption of meat" — was replaced by artful compromise: "Choose meats, poultry and fish that will reduce saturated-fat intake."

A subtle change in emphasis, you might say, but a world of difference just the same. First, the stark message to "eat less" of a particular food has been deep-sixed; don't look for it ever again in any official U.S. dietary pronouncement. Second, notice how distinctions between entities as different as fish and beef and chicken have collapsed; those three venerable foods, each representing an entirely different taxonomic class, are now lumped together as delivery systems for a single nutrient. Notice too how the new language exonerates the foods themselves; now the culprit is an obscure, invisible, tasteless — and politically unconnected — substance that may or may not lurk in them called "saturated fat."

The linguistic capitulation did nothing to rescue McGovern from his blunder; the very next election, in 1980, the beef lobby helped rusticate the three-term senator, sending an unmistakable warning to anyone who would challenge the American diet, and in particular the big chunk of animal protein sitting in the middle of its plate. Henceforth, government dietary guidelines would shun plain talk about whole foods, each of which has its trade association on Capitol Hill, and would instead arrive clothed in scientific euphemism and speaking of nutrients, entities that few Americans really understood but that lack powerful lobbies in Washington. This was precisely the tack taken by the National Academy of Sciences when it issued its landmark report on diet and cancer in 1982. Organized nutrient by nutrient in a way guaranteed to offend no food group, it codified the official new dietary language. Industry and media followed suit, and terms like polyunsaturated, cholesterol, monounsaturated, carbohydrate, fiber, polyphenols, amino acids and carotenes soon colonized much of the cultural space previously occupied by the tangible substance formerly known as food. The Age of Nutritionism had arrived.

THE RISE OF NUTRITIONISM

The first thing to understand about nutritionism — I first encountered the term in the work of an Australian sociologist of science named Gyorgy Scrinis — is that it is not quite the same as nutrition. As the "ism" suggests, it is not a scientific subject but an ideology. Ideologies are ways of organizing large swaths of life and experience under a set of shared but unexamined assumptions. This quality makes an ideology particularly hard to see, at least while it's exerting its hold on your culture. A reigning ideology is a little like the weather, all pervasive and virtually inescapable. Still, we can try.

In the case of nutritionism, the widely shared but unexamined assumption is that the key to understanding food is indeed the nutrient. From this basic premise flow several others. Since nutrients, as compared with foods, are invisible and therefore slightly mysterious, it falls to the scientists (and to the journalists through whom the scientists speak) to explain the hidden reality of foods to us. To enter a world in which you dine on unseen nutrients, you need lots of expert help.

But expert help to do what, exactly? This brings us to another unexamined assumption: that the whole point of eating is to maintain and promote bodily health. Hippocrates's famous injunction to "let food be thy medicine" is ritually invoked to support this notion. I'll leave the premise alone for now, except to point out that it is not shared by all cultures and that the experience of these other cultures suggests that, paradoxically, viewing food as being about things other than bodily health — like pleasure, say, or socializing — makes people no less healthy; indeed, there's some reason to believe that it may make them more healthy. This is what we usually have in mind when we speak of the "French paradox" — the fact that a population that eats all sorts of unhealthful nutrients is in many ways healthier than we Americans are. So there is at least a question as to whether nutritionism is actually any good for you.

Another potentially serious weakness of nutritionist ideology is that it has trouble discerning qualitative distinctions between foods. So fish, beef and chicken through the nutritionists' lens become mere delivery systems for varying quantities of fats and proteins and whatever other nutrients are on their scope. Similarly, any qualitative distinctions between processed foods and whole foods disappear when your focus is on quantifying the nutrients they contain (or, more precisely, the known nutrients).

This is a great boon for manufacturers of processed food, and it helps explain why they have been so happy to get with the nutritionism program. In the years following McGovern's capitulation and the 1982 National Academy report, the food industry set about re-engineering thousands of popular food products to contain more of the nutrients that science and government had deemed the good ones and less of the bad, and by the late '80s a golden era of food science was upon us. The Year of Eating Oat Bran — also known as 1988 — served as a kind of coming-out party for the food scientists, who succeeded in getting the material into nearly every processed food sold in America. Oat bran's moment on the dietary stage didn't last long, but the pattern had been established, and every few years since then a new oat bran has taken its turn under the marketing lights. (Here comes omega-3!)

By comparison, the typical real food has more trouble competing under the rules of nutritionism, if only because something like a banana or an avocado can't easily change its nutritional stripes (though rest assured the genetic engineers are hard at work on the problem). So far, at least, you can't put oat bran in a banana. So depending on the reigning nutritional orthodoxy, the avocado might be either a high-fat food to be avoided (Old Think) or a food high in monounsaturated fat to be embraced (New Think). The fate of each whole food rises and falls with every change in the nutritional weather, while the processed foods are simply reformulated. That's why when the Atkins mania hit the food industry, bread and pasta were given a quick redesign (dialing back the carbs; boosting the protein), while the poor unreconstructed potatoes and carrots were left out in the cold.

Of course it's also a lot easier to slap a health claim on a box of sugary cereal than on a potato or carrot, with the perverse result that the most healthful foods in the supermarket sit there quietly in the produce section, silent as stroke victims, while a few aisles over, the Cocoa Puffs and Lucky Charms are screaming about their newfound whole-grain goodness.

EAT RIGHT, GET FATTER

So nutritionism is good for business. But is it good for us? You might think that a national fixation on nutrients would lead to measurable improvements in the public health. But for that to happen, the underlying nutritional science, as well as the policy recommendations (and the journalism) based on that science, would have to be sound. This has seldom been the case.

Consider what happened immediately after the 1977 "Dietary Goals" — McGovern's masterpiece of politico-nutritionist compromise. In the wake of the panel's recommendation that we cut down on saturated fat, a recommendation seconded by the 1982 National Academy report on cancer, Americans did indeed change their diets, endeavoring for a quarter-century to do what they had been told. Well, kind of. The industrial food supply was promptly reformulated to reflect the official advice, giving us low-fat pork, low-fat Snackwell's and all the low-fat pasta and high-fructose (yet low-fat!) corn syrup we could consume. Which turned out to be quite a lot. Oddly, America got really fat on its new low-fat diet — indeed, many date the current obesity and diabetes epidemic to the late 1970s, when Americans began binging on carbohydrates, ostensibly as a way to avoid the evils of fat.

This story has been told before, notably in these pages ("What if It's All Been a Big Fat Lie?" by Gary Taubes, July 7, 2002), but it's a little more complicated than the official version suggests. In that version, which inspired the most recent Atkins craze, we were told that America got fat when, responding to bad scientific advice, it shifted its diet from fats to carbs, suggesting that a re-evaluation of the two nutrients is in order: fat doesn't make you fat; carbs do. (Why this should have come as news is a mystery: as long as people have been raising animals for food, they have fattened them on carbs.)

But there are a couple of problems with this revisionist picture. First, while it is true that Americans post-1977 did begin binging on carbs, and that fat as a percentage of total calories in the American diet declined, we never did in fact cut down on our consumption of fat. Meat consumption actually climbed. We just heaped a bunch more carbs onto our plates, obscuring perhaps, but not replacing, the expanding chunk of animal protein squatting in the center.

How did that happen? I would submit that the ideology of nutritionism deserves as much of the blame as the carbohydrates themselves do — that and human nature. By framing dietary advice in terms of good and bad nutrients, and by burying the recommendation that we should eat less of any particular food, it was easy for the take-home message of the 1977 and 1982 dietary guidelines to be simplified as follows: Eat more low-fat foods. And that is what we did. We're always happy to receive a dispensation to eat more of something (with the possible exception of oat bran), and one of the things nutritionism reliably gives us is some such dispensation: low-fat cookies then, low-carb beer now. It's hard to imagine the low-fat craze taking off as it did if McGovern's original food-based recommendations had stood: eat fewer meat and dairy products. For how do you get from that stark counsel to the idea that another case of Snackwell's is just what the doctor ordered?

BAD SCIENCE

But if nutritionism leads to a kind of false consciousness in the mind of the eater, the ideology can just as easily mislead the scientist. Most nutritional science involves studying one nutrient at a time, an approach that even nutritionists who do it will tell you is deeply flawed. "The problem with nutrient-by-nutrient nutrition science," points out Marion Nestle, the New York University nutritionist, "is that it takes the nutrient out of the context of food, the food out of the context of diet and the diet out of the context of lifestyle."

If nutritional scientists know this, why do they do it anyway? Because a nutrient bias is built into the way science is done: scientists need individual variables they can isolate. Yet even the simplest food is a hopelessly complex thing to study, a virtual wilderness of chemical compounds, many of which exist in complex and dynamic relation to one another, and all of which together are in the process of changing from one state to another. So if you're a nutritional scientist, you do the only thing you can do, given the tools at your disposal: break the thing down into its component parts and study those one by one, even if that means ignoring complex interactions and contexts, as well as the fact that the whole may be more than, or just different from, the sum of its parts. This is what we mean by reductionist science.

Scientific reductionism is an undeniably powerful tool, but it can mislead us too, especially when applied to something as complex as, on the one side, a food, and on the other, a human eater. It encourages us to take a mechanistic view of that transaction: put in this nutrient; get out that physiological result. Yet people differ in important ways. Some populations can metabolize sugars better than others; depending on your evolutionary heritage, you may or may not be able to digest the lactose in milk. The specific ecology of your intestines helps determine how efficiently you digest what you eat, so that the same input of 100 calories may yield more or less energy depending on the proportion of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes living in your gut. There is nothing very machinelike about the human eater, and so to think of food as simply fuel is wrong.

Also, people don't eat nutrients, they eat foods, and foods can behave very differently than the nutrients they contain. Researchers have long believed, based on epidemiological comparisons of different populations, that a diet high in fruits and vegetables confers some protection against cancer. So naturally they ask, What nutrients in those plant foods are responsible for that effect? One hypothesis is that the antioxidants in fresh produce — compounds like beta carotene, lycopene, vitamin E, etc. — are the X factor. It makes good sense: these molecules (which plants produce to protect themselves from the highly reactive oxygen atoms produced in photosynthesis) vanquish the free radicals in our bodies, which can damage DNA and initiate cancers. At least that's how it seems to work in the test tube. Yet as soon as you remove these useful molecules from the context of the whole foods they're found in, as we've done in creating antioxidant supplements, they don't work at all. Indeed, in the case of beta carotene ingested as a supplement, scientists have discovered that it actually increases the risk of certain cancers. Big oops.

What's going on here? We don't know. It could be the vagaries of human digestion. Maybe the fiber (or some other component) in a carrot protects the antioxidant molecules from destruction by stomach acids early in the digestive process. Or it could be that we isolated the wrong antioxidant. Beta is just one of a whole slew of carotenes found in common vegetables; maybe we focused on the wrong one. Or maybe beta carotene works as an antioxidant only in concert with some other plant chemical or process; under other circumstances, it may behave as a pro-oxidant.

Indeed, to look at the chemical composition of any common food plant is to realize just how much complexity lurks within it. Here's a list of just the antioxidants that have been identified in garden-variety thyme:

4-Terpineol, alanine, anethole, apigenin, ascorbic acid, beta carotene, caffeic acid, camphene, carvacrol, chlorogenic acid, chrysoeriol, eriodictyol, eugenol, ferulic acid, gallic acid, gamma-terpinene isochlorogenic acid, isoeugenol, isothymonin, kaempferol, labiatic acid, lauric acid, linalyl acetate, luteolin, methionine, myrcene, myristic acid, naringenin, oleanolic acid, p-coumoric acid, p-hydroxy-benzoic acid, palmitic acid, rosmarinic acid, selenium, tannin, thymol, tryptophan, ursolic acid, vanillic acid.

This is what you're ingesting when you eat food flavored with thyme. Some of these chemicals are broken down by your digestion, but others are going on to do undetermined things to your body: turning some gene's expression on or off, perhaps, or heading off a free radical before it disturbs a strand of DNA deep in some cell. It would be great to know how this all works, but in the meantime we can enjoy thyme in the knowledge that it probably doesn't do any harm (since people have been eating it forever) and that it may actually do some good (since people have been eating it forever) and that even if it does nothing, we like the way it tastes.

It's also important to remind ourselves that what reductive science can manage to perceive well enough to isolate and study is subject to change, and that we have a tendency to assume that what we can see is all there is to see. When William Prout isolated the big three macronutrients, scientists figured they now understood food and what the body needs from it; when the vitamins were isolated a few decades later, scientists thought, O.K., now we really understand food and what the body needs to be healthy; today it's the polyphenols and carotenoids that seem all-important. But who knows what the hell else is going on deep in the soul of a carrot?

The good news is that, to the carrot eater, it doesn't matter. That's the great thing about eating food as compared with nutrients: you don't need to fathom a carrot's complexity to reap its benefits.

The case of the antioxidants points up the dangers in taking a nutrient out of the context of food; as Nestle suggests, scientists make a second, related error when they study the food out of the context of the diet. We don't eat just one thing, and when we are eating any one thing, we're not eating another. We also eat foods in combinations and in orders that can affect how they're absorbed. Drink coffee with your steak, and your body won't be able to fully absorb the iron in the meat. The trace of limestone in the corn tortilla unlocks essential amino acids in the corn that would otherwise remain unavailable. Some of those compounds in that sprig of thyme may well affect my digestion of the dish I add it to, helping to break down one compound or possibly stimulate production of an enzyme to detoxify another. We have barely begun to understand the relationships among foods in a cuisine.

But we do understand some of the simplest relationships, like the zero-sum relationship: that if you eat a lot of meat you're probably not eating a lot of vegetables. This simple fact may explain why populations that eat diets high in meat have higher rates of coronary heart disease and cancer than those that don't. Yet nutritionism encourages us to look elsewhere for the explanation: deep within the meat itself, to the culpable nutrient, which scientists have long assumed to be the saturated fat. So they are baffled when large-population studies, like the Women's Health Initiative, fail to find that reducing fat intake significantly reduces the incidence of heart disease or cancer.

Of course thanks to the low-fat fad (inspired by the very same reductionist fat hypothesis), it is entirely possible to reduce your intake of saturated fat without significantly reducing your consumption of animal protein: just drink the low-fat milk and order the skinless chicken breast or the turkey bacon. So maybe the culprit nutrient in meat and dairy is the animal protein itself, as some researchers now hypothesize. (The Cornell nutritionist T. Colin Campbell argues as much in his recent book, "The China Study.") Or, as the Harvard epidemiologist Walter C. Willett suggests, it could be the steroid hormones typically present in the milk and meat; these hormones (which occur naturally in meat and milk but are often augmented in industrial production) are known to promote certain cancers.

But people worried about their health needn't wait for scientists to settle this question before deciding that it might be wise to eat more plants and less meat. This is of course precisely what the McGovern committee was trying to tell us.

Nestle also cautions against taking the diet out of the context of the lifestyle. The Mediterranean diet is widely believed to be one of the most healthful ways to eat, yet much of what we know about it is based on studies of people living on the island of Crete in the 1950s, who in many respects lived lives very different from our own. Yes, they ate lots of olive oil and little meat. But they also did more physical labor. They fasted regularly. They ate a lot of wild greens — weeds. And, perhaps most important, they consumed far fewer total calories than we do. Similarly, much of what we know about the health benefits of a vegetarian diet is based on studies of Seventh Day Adventists, who muddy the nutritional picture by drinking absolutely no alcohol and never smoking. These extraneous but unavoidable factors are called, aptly, "confounders." One last example: People who take supplements are healthier than the population at large, but their health probably has nothing whatsoever to do with the supplements they take — which recent studies have suggested are worthless. Supplement-takers are better-educated, more-affluent people who, almost by definition, take a greater-than-normal interest in personal health — confounding factors that probably account for their superior health.

But if confounding factors of lifestyle bedevil comparative studies of different populations, the supposedly more rigorous "prospective" studies of large American populations suffer from their own arguably even more disabling flaws. In these studies — of which the Women's Health Initiative is the best known — a large population is divided into two groups. The intervention group changes its diet in some prescribed manner, while the control group does not. The two groups are then tracked over many years to learn whether the intervention affects relative rates of chronic disease.

When it comes to studying nutrition, this sort of extensive, long-term clinical trial is supposed to be the gold standard. It certainly sounds sound. In the case of the Women's Health Initiative, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, the eating habits and health outcomes of nearly 49,000 women (ages 50 to 79 at the beginning of the study) were tracked for eight years. One group of the women were told to reduce their consumption of fat to 20 percent of total calories. The results were announced early last year, producing front-page headlines of which the one in this newspaper was typical: "Low-Fat Diet Does Not Cut Health Risks, Study Finds." And the cloud of nutritional confusion over the country darkened.

But even a cursory analysis of the study's methods makes you wonder why anyone would take such a finding seriously, let alone order a Quarter Pounder With Cheese to celebrate it, as many newspaper readers no doubt promptly went out and did. Even the beginner student of nutritionism will immediately spot several flaws: the focus was on "fat," rather than on any particular food, like meat or dairy. So women could comply simply by switching to lower-fat animal products. Also, no distinctions were made between types of fat: women getting their allowable portion of fat from olive oil or fish were lumped together with woman getting their fat from low-fat cheese or chicken breasts or margarine. Why? Because when the study was designed 16 years ago, the whole notion of "good fats" was not yet on the scientific scope. Scientists study what scientists can see.

But perhaps the biggest flaw in this study, and other studies like it, is that we have no idea what these women were really eating because, like most people when asked about their diet, they lied about it. How do we know this? Deduction. Consider: When the study began, the average participant weighed in at 170 pounds and claimed to be eating 1,800 calories a day. It would take an unusual metabolism to maintain that weight on so little food. And it would take an even freakier metabolism to drop only one or two pounds after getting down to a diet of 1,400 to 1,500 calories a day — as the women on the "low-fat" regimen claimed to have done. Sorry, ladies, but I just don't buy it.

In fact, nobody buys it. Even the scientists who conduct this sort of research conduct it in the knowledge that people lie about their food intake all the time. They even have scientific figures for the magnitude of the lie. Dietary trials like the Women's Health Initiative rely on "food-frequency questionnaires," and studies suggest that people on average eat between a fifth and a third more than they claim to on the questionnaires. How do the researchers know that? By comparing what people report on questionnaires with interviews about their dietary intake over the previous 24 hours, thought to be somewhat more reliable. In fact, the magnitude of the lie could be much greater, judging by the huge disparity between the total number of food calories produced every day for each American (3,900 calories) and the average number of those calories Americans own up to chomping: 2,000. (Waste accounts for some of the disparity, but nowhere near all of it.) All we really know about how much people actually eat is that the real number lies somewhere between those two figures.

To try to fill out the food-frequency questionnaire used by the Women's Health Initiative, as I recently did, is to realize just how shaky the data on which such trials rely really are. The survey, which took about 45 minutes to complete, started off with some relatively easy questions: "Did you eat chicken or turkey during the last three months?" Having answered yes, I was then asked, "When you ate chicken or turkey, how often did you eat the skin?" But the survey soon became harder, as when it asked me to think back over the past three months to recall whether when I ate okra, squash or yams, they were fried, and if so, were they fried in stick margarine, tub margarine, butter, "shortening" (in which category they inexplicably lump together hydrogenated vegetable oil and lard), olive or canola oil or nonstick spray? I honestly didn't remember, and in the case of any okra eaten in a restaurant, even a hypnotist could not get out of me what sort of fat it was fried in. In the meat section, the portion sizes specified haven't been seen in America since the Hoover administration. If a four-ounce portion of steak is considered "medium," was I really going to admit that the steak I enjoyed on an unrecallable number of occasions during the past three months was probably the equivalent of two or three (or, in the case of a steakhouse steak, no less than four) of these portions? I think not. In fact, most of the "medium serving sizes" to which I was asked to compare my own consumption made me feel piggish enough to want to shave a few ounces here, a few there. (I mean, I wasn't under oath or anything, was I?)

This is the sort of data on which the largest questions of diet and health are being decided in America today.

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

In the end, the biggest, most ambitious and widely reported studies of diet and health leave more or less undisturbed the main features of the Western diet: lots of meat and processed foods, lots of added fat and sugar, lots of everything — except fruits, vegetables and whole grains. In keeping with the nutritionism paradigm and the limits of reductionist science, the researchers fiddle with single nutrients as best they can, but the populations they recruit and study are typical American eaters doing what typical American eaters do: trying to eat a little less of this nutrient, a little more of that, depending on the latest thinking. (One problem with the control groups in these studies is that they too are exposed to nutritional fads in the culture, so over time their eating habits come to more closely resemble the habits of the intervention group.) It should not surprise us that the findings of such research would be so equivocal and confusing.

But what about the elephant in the room — the Western diet? It might be useful, in the midst of our deepening confusion about nutrition, to review what we do know about diet and health. What we know is that people who eat the way we do in America today suffer much higher rates of cancer, heart disease, diabetes and obesity than people eating more traditional diets. (Four of the 10 leading killers in America are linked to diet.) Further, we know that simply by moving to America, people from nations with low rates of these "diseases of affluence" will quickly acquire them. Nutritionism by and large takes the Western diet as a given, seeking to moderate its most deleterious effects by isolating the bad nutrients in it — things like fat, sugar, salt — and encouraging the public and the food industry to limit them. But after several decades of nutrient-based health advice, rates of cancer and heart disease in the U.S. have declined only slightly (mortality from heart disease is down since the '50s, but this is mainly because of improved treatment), and rates of obesity and diabetes have soared.

No one likes to admit that his or her best efforts at understanding and solving a problem have actually made the problem worse, but that's exactly what has happened in the case of nutritionism. Scientists operating with the best of intentions, using the best tools at their disposal, have taught us to look at food in a way that has diminished our pleasure in eating it while doing little or nothing to improve our health. Perhaps what we need now is a broader, less reductive view of what food is, one that is at once more ecological and cultural. What would happen, for example, if we were to start thinking about food as less of a thing and more of a relationship?

In nature, that is of course precisely what eating has always been: relationships among species in what we call food chains, or webs, that reach all the way down to the soil. Species co-evolve with the other species they eat, and very often a relationship of interdependence develops: I'll feed you if you spread around my genes. A gradual process of mutual adaptation transforms something like an apple or a squash into a nutritious and tasty food for a hungry animal. Over time and through trial and error, the plant becomes tastier (and often more conspicuous) in order to gratify the animal's needs and desires, while the animal gradually acquires whatever digestive tools (enzymes, etc.) are needed to make optimal use of the plant. Similarly, cow's milk did not start out as a nutritious food for humans; in fact, it made them sick until humans who lived around cows evolved the ability to digest lactose as adults. This development proved much to the advantage of both the milk drinkers and the cows.

"Health" is, among other things, the byproduct of being involved in these sorts of relationships in a food chain — involved in a great many of them, in the case of an omnivorous creature like us. Further, when the health of one link of the food chain is disturbed, it can affect all the creatures in it. When the soil is sick or in some way deficient, so will be the grasses that grow in that soil and the cattle that eat the grasses and the people who drink the milk. Or, as the English agronomist Sir Albert Howard put it in 1945 in "The Soil and Health" (a founding text of organic agriculture), we would do well to regard "the whole problem of health in soil, plant, animal and man as one great subject." Our personal health is inextricably bound up with the health of the entire food web.

In many cases, long familiarity between foods and their eaters leads to elaborate systems of communications up and down the food chain, so that a creature's senses come to recognize foods as suitable by taste and smell and color, and our bodies learn what to do with these foods after they pass the test of the senses, producing in anticipation the chemicals necessary to break them down. Health depends on knowing how to read these biological signals: this smells spoiled; this looks ripe; that's one good-looking cow. This is easier to do when a creature has long experience of a food, and much harder when a food has been designed expressly to deceive its senses — with artificial flavors, say, or synthetic sweeteners.

Note that these ecological relationships are between eaters and whole foods, not nutrients. Even though the foods in question eventually get broken down in our bodies into simple nutrients, as corn is reduced to simple sugars, the qualities of the whole food are not unimportant — they govern such things as the speed at which the sugars will be released and absorbed, which we're coming to see as critical to insulin metabolism. Put another way, our bodies have a longstanding and sustainable relationship to corn that we do not have to high-fructose corn syrup. Such a relationship with corn syrup might develop someday (as people evolve superhuman insulin systems to cope with regular floods of fructose and glucose), but for now the relationship leads to ill health because our bodies don't know how to handle these biological novelties. In much the same way, human bodies that can cope with chewing coca leaves — a longstanding relationship between native people and the coca plant in South America — cannot cope with cocaine or crack, even though the same "active ingredients" are present in all three. Reductionism as a way of understanding food or drugs may be harmless, even necessary, but reductionism in practice can lead to problems.

Looking at eating through this ecological lens opens a whole new perspective on exactly what the Western diet is: a radical and rapid change not just in our foodstuffs over the course of the 20th century but also in our food relationships, all the way from the soil to the meal. The ideology of nutritionism is itself part of that change. To get a firmer grip on the nature of those changes is to begin to know how we might make our relationships to food healthier. These changes have been numerous and far-reaching, but consider as a start these four large-scale ones:

From Whole Foods to Refined. The case of corn points up one of the key features of the modern diet: a shift toward increasingly refined foods, especially carbohydrates. Call it applied reductionism. Humans have been refining grains since at least the Industrial Revolution, favoring white flour (and white rice) even at the price of lost nutrients. Refining grains extends their shelf life (precisely because it renders them less nutritious to pests) and makes them easier to digest, by removing the fiber that ordinarily slows the release of their sugars. Much industrial food production involves an extension and intensification of this practice, as food processors find ways to deliver glucose — the brain's preferred fuel — ever more swiftly and efficiently. Sometimes this is precisely the point, as when corn is refined into corn syrup; other times it is an unfortunate byproduct of food processing, as when freezing food destroys the fiber that would slow sugar absorption.

So fast food is fast in this other sense too: it is to a considerable extent predigested, in effect, and therefore more readily absorbed by the body. But while the widespread acceleration of the Western diet offers us the instant gratification of sugar, in many people (and especially those newly exposed to it) the "speediness" of this food overwhelms the insulin response and leads to Type II diabetes. As one nutrition expert put it to me, we're in the middle of "a national experiment in mainlining glucose." To encounter such a diet for the first time, as when people accustomed to a more traditional diet come to America, or when fast food comes to their countries, delivers a shock to the system. Public-health experts call it "the nutrition transition," and it can be deadly.

From Complexity to Simplicity. If there is one word that covers nearly all the changes industrialization has made to the food chain, it would be simplification. Chemical fertilizers simplify the chemistry of the soil, which in turn appears to simplify the chemistry of the food grown in that soil. Since the widespread adoption of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers in the 1950s, the nutritional quality of produce in America has, according to U.S.D.A. figures, declined significantly. Some researchers blame the quality of the soil for the decline; others cite the tendency of modern plant breeding to select for industrial qualities like yield rather than nutritional quality. Whichever it is, the trend toward simplification of our food continues on up the chain. Processing foods depletes them of many nutrients, a few of which are then added back in through "fortification": folic acid in refined flour, vitamins and minerals in breakfast cereal. But food scientists can add back only the nutrients food scientists recognize as important. What are they overlooking?

Simplification has occurred at the level of species diversity, too. The astounding variety of foods on offer in the modern supermarket obscures the fact that the actual number of species in the modern diet is shrinking. For reasons of economics, the food industry prefers to tease its myriad processed offerings from a tiny group of plant species, corn and soybeans chief among them. Today, a mere four crops account for two-thirds of the calories humans eat. When you consider that humankind has historically consumed some 80,000 edible species, and that 3,000 of these have been in widespread use, this represents a radical simplification of the food web. Why should this matter? Because humans are omnivores, requiring somewhere between 50 and 100 different chemical compounds and elements to be healthy. It's hard to believe that we can get everything we need from a diet consisting largely of processed corn, soybeans, wheat and rice.

From Leaves to Seeds. It's no coincidence that most of the plants we have come to rely on are grains; these crops are exceptionally efficient at transforming sunlight into macronutrients — carbs, fats and proteins. These macronutrients in turn can be profitably transformed into animal protein (by feeding them to animals) and processed foods of every description. Also, the fact that grains are durable seeds that can be stored for long periods means they can function as commodities as well as food, making these plants particularly well suited to the needs of industrial capitalism.

The needs of the human eater are another matter. An oversupply of macronutrients, as we now have, itself represents a serious threat to our health, as evidenced by soaring rates of obesity and diabetes. But the undersupply of micronutrients may constitute a threat just as serious. Put in the simplest terms, we're eating a lot more seeds and a lot fewer leaves, a tectonic dietary shift the full implications of which we are just beginning to glimpse. If I may borrow the nutritionist's reductionist vocabulary for a moment, there are a host of critical micronutrients that are harder to get from a diet of refined seeds than from a diet of leaves. There are the antioxidants and all the other newly discovered phytochemicals (remember that sprig of thyme?); there is the fiber, and then there are the healthy omega-3 fats found in leafy green plants, which may turn out to be most important benefit of all.

Most people associate omega-3 fatty acids with fish, but fish get them from green plants (specifically algae), which is where they all originate. Plant leaves produce these essential fatty acids ("essential" because our bodies can't produce them on their own) as part of photosynthesis. Seeds contain more of another essential fatty acid: omega-6. Without delving too deeply into the biochemistry, the two fats perform very different functions, in the plant as well as the plant eater. Omega-3s appear to play an important role in neurological development and processing, the permeability of cell walls, the metabolism of glucose and the calming of inflammation. Omega-6s are involved in fat storage (which is what they do for the plant), the rigidity of cell walls, clotting and the inflammation response. (Think of omega-3s as fleet and flexible, omega-6s as sturdy and slow.) Since the two lipids compete with each other for the attention of important enzymes, the ratio between omega-3s and omega-6s may matter more than the absolute quantity of either fat. Thus too much omega-6 may be just as much a problem as too little omega-3.

And that might well be a problem for people eating a Western diet. As we've shifted from leaves to seeds, the ratio of omega-6s to omega-3s in our bodies has shifted, too. At the same time, modern food-production practices have further diminished the omega-3s in our diet. Omega-3s, being less stable than omega-6s, spoil more readily, so we have selected for plants that produce fewer of them; further, when we partly hydrogenate oils to render them more stable, omega-3s are eliminated. Industrial meat, raised on seeds rather than leaves, has fewer omega-3s and more omega-6s than preindustrial meat used to have. And official dietary advice since the 1970s has promoted the consumption of polyunsaturated vegetable oils, most of which are high in omega-6s (corn and soy, especially). Thus, without realizing what we were doing, we significantly altered the ratio of these two essential fats in our diets and bodies, with the result that the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 in the typical American today stands at more than 10 to 1; before the widespread introduction of seed oils at the turn of the last century, it was closer to 1 to 1.

The role of these lipids is not completely understood, but many researchers say that these historically low levels of omega-3 (or, conversely, high levels of omega-6) bear responsibility for many of the chronic diseases associated with the Western diet, especially heart disease and diabetes. (Some researchers implicate omega-3 deficiency in rising rates of depression and learning disabilities as well.) To remedy this deficiency, nutritionism classically argues for taking omega-3 supplements or fortifying food products, but because of the complex, competitive relationship between omega-3 and omega-6, adding more omega-3s to the diet may not do much good unless you also reduce your intake of omega-6.

From Food Culture to Food Science. The last important change wrought by the Western diet is not, strictly speaking, ecological. But the industrialization of our food that we call the Western diet is systematically destroying traditional food cultures. Before the modern food era — and before nutritionism — people relied for guidance about what to eat on their national or ethnic or regional cultures. We think of culture as a set of beliefs and practices to help mediate our relationship to other people, but of course culture (at least before the rise of science) has also played a critical role in helping mediate people's relationship to nature. Eating being a big part of that relationship, cultures have had a great deal to say about what and how and why and when and how much we should eat. Of course when it comes to food, culture is really just a fancy word for Mom, the figure who typically passes on the food ways of the group — food ways that, although they were never "designed" to optimize health (we have many reasons to eat the way we do), would not have endured if they did not keep eaters alive and well.

The sheer novelty and glamour of the Western diet, with its 17,000 new food products introduced every year, and the marketing muscle used to sell these products, has overwhelmed the force of tradition and left us where we now find ourselves: relying on science and journalism and marketing to help us decide questions about what to eat. Nutritionism, which arose to help us better deal with the problems of the Western diet, has largely been co-opted by it, used by the industry to sell more food and to undermine the authority of traditional ways of eating. You would not have read this far into this article if your food culture were intact and healthy; you would simply eat the way your parents and grandparents and great-grandparents taught you to eat. The question is, Are we better off with these new authorities than we were with the traditional authorities they supplanted? The answer by now should be clear.

It might be argued that, at this point in history, we should simply accept that fast food is our food culture. Over time, people will get used to eating this way and our health will improve. But for natural selection to help populations adapt to the Western diet, we'd have to be prepared to let those whom it sickens die. That's not what we're doing. Rather, we're turning to the health-care industry to help us "adapt." Medicine is learning how to keep alive the people whom the Western diet is making sick. It's gotten good at extending the lives of people with heart disease, and now it's working on obesity and diabetes. Capitalism is itself marvelously adaptive, able to turn the problems it creates into lucrative business opportunities: diet pills, heart-bypass operations, insulin pumps, bariatric surgery. But while fast food may be good business for the health-care industry, surely the cost to society — estimated at more than $200 billion a year in diet-related health-care costs — is unsustainable.

BEYOND NUTRITIONISM

To medicalize the diet problem is of course perfectly consistent with nutritionism. So what might a more ecological or cultural approach to the problem recommend? How might we plot our escape from nutritionism and, in turn, from the deleterious effects of the modern diet? In theory nothing could be simpler — stop thinking and eating that way — but this is somewhat harder to do in practice, given the food environment we now inhabit and the loss of sharp cultural tools to guide us through it. Still, I do think escape is possible, to which end I can now revisit — and elaborate on, but just a little — the simple principles of healthy eating I proposed at the beginning of this essay, several thousand words ago. So try these few (flagrantly unscientific) rules of thumb, collected in the course of my nutritional odyssey, and see if they don't at least point us in the right direction.

1. Eat food. Though in our current state of confusion, this is much easier said than done. So try this: Don't eat anything your great-great-grandmother wouldn't recognize as food. (Sorry, but at this point Moms are as confused as the rest of us, which is why we have to go back a couple of generations, to a time before the advent of modern food products.) There are a great many foodlike items in the supermarket your ancestors wouldn't recognize as food (Go-Gurt? Breakfast-cereal bars? Nondairy creamer?); stay away from these.

2. Avoid even those food products that come bearing health claims. They're apt to be heavily processed, and the claims are often dubious at best. Don't forget that margarine, one of the first industrial foods to claim that it was more healthful than the traditional food it replaced, turned out to give people heart attacks. When Kellogg's can boast about its Healthy Heart Strawberry Vanilla cereal bars, health claims have become hopelessly compromised. (The American Heart Association charges food makers for their endorsement.) Don't take the silence of the yams as a sign that they have nothing valuable to say about health.

3. Especially avoid food products containing ingredients that are a) unfamiliar, b) unpronounceable c) more than five in number — or that contain high-fructose corn syrup.None of these characteristics are necessarily harmful in and of themselves, but all of them are reliable markers for foods that have been highly processed.

4. Get out of the supermarket whenever possible. You won't find any high-fructose corn syrup at the farmer's market; you also won't find food harvested long ago and far away. What you will find are fresh whole foods picked at the peak of nutritional quality. Precisely the kind of food your great-great-grandmother would have recognized as food.

5. Pay more, eat less. The American food system has for a century devoted its energies and policies to increasing quantity and reducing price, not to improving quality. There's no escaping the fact that better food — measured by taste or nutritional quality (which often correspond) — costs more, because it has been grown or raised less intensively and with more care. Not everyone can afford to eat well in America, which is shameful, but most of us can: Americans spend, on average, less than 10 percent of their income on food, down from 24 percent in 1947, and less than the citizens of any other nation. And those of us who can afford to eat well should. Paying more for food well grown in good soils — whether certified organic or not — will contribute not only to your health (by reducing exposure to pesticides) but also to the health of others who might not themselves be able to afford that sort of food: the people who grow it and the people who live downstream, and downwind, of the farms where it is grown.

"Eat less" is the most unwelcome advice of all, but in fact the scientific case for eating a lot less than we currently do is compelling. "Calorie restriction" has repeatedly been shown to slow aging in animals, and many researchers (including Walter Willett, the Harvard epidemiologist) believe it offers the single strongest link between diet and cancer prevention. Food abundance is a problem, but culture has helped here, too, by promoting the idea of moderation. Once one of the longest-lived people on earth, the Okinawans practiced a principle they called "Hara Hachi Bu": eat until you are 80 percent full. To make the "eat less" message a bit more palatable, consider that quality may have a bearing on quantity: I don't know about you, but the better the quality of the food I eat, the less of it I need to feel satisfied. All tomatoes are not created equal.

6. Eat mostly plants, especially leaves. Scientists may disagree on what's so good about plants — the antioxidants? Fiber? Omega-3s? — but they do agree that they're probably really good for you and certainly can't hurt. Also, by eating a plant-based diet, you'll be consuming far fewer calories, since plant foods (except seeds) are typically less "energy dense" than the other things you might eat. Vegetarians are healthier than carnivores, but near vegetarians ("flexitarians") are as healthy as vegetarians. Thomas Jefferson was on to something when he advised treating meat more as a flavoring than a food.

7. Eat more like the French. Or the Japanese. Or the Italians. Or the Greeks. Confounding factors aside, people who eat according to the rules of a traditional food culture are generally healthier than we are. Any traditional diet will do: if it weren't a healthy diet, the people who follow it wouldn't still be around. True, food cultures are embedded in societies and economies and ecologies, and some of them travel better than others: Inuit not so well as Italian. In borrowing from a food culture, pay attention to how a culture eats, as well as to what it eats. In the case of the French paradox, it may not be the dietary nutrients that keep the French healthy (lots of saturated fat and alcohol?!) so much as the dietary habits: small portions, no seconds or snacking, communal meals — and the serious pleasure taken in eating. (Worrying about diet can't possibly be good for you.) Let culture be your guide, not science.

8. Cook. And if you can, plant a garden. To take part in the intricate and endlessly interesting processes of providing for our sustenance is the surest way to escape the culture of fast food and the values implicit in it: that food should be cheap and easy; that food is fuel and not communion. The culture of the kitchen, as embodied in those enduring traditions we call cuisines, contains more wisdom about diet and health than you are apt to find in any nutrition journal or journalism. Plus, the food you grow yourself contributes to your health long before you sit down to eat it. So you might want to think about putting down this article now and picking up a spatula or hoe.

9. Eat like an omnivore. Try to add new species, not just new foods, to your diet. The greater the diversity of species you eat, the more likely you are to cover all your nutritional bases. That of course is an argument from nutritionism, but there is a better one, one that takes a broader view of "health." Biodiversity in the diet means less monoculture in the fields. What does that have to do with your health? Everything. The vast monocultures that now feed us require tremendous amounts of chemical fertilizers and pesticides to keep from collapsing. Diversifying those fields will mean fewer chemicals, healthier soils, healthier plants and animals and, in turn, healthier people. It's all connected, which is another way of saying that your health isn't bordered by your body and that what's good for the soil is probably good for you, too.

Michael Pollan, a contributing writer, is the Knight professor of journalism at the University of California, Berkeley. His most recent book, "The Omnivore's Dilemma," was chosen by the editors of The New York Times Book Review as one of the 10 best books of 2006.

Great 1969 video of Desmond Dekker performing "The Israelites"

Great 1969 video of Desmond Dekker performing "The Israelites"  Check out Roadrace, the "Citizen Kane of Hot Wheels car chase videos," according to COOP!

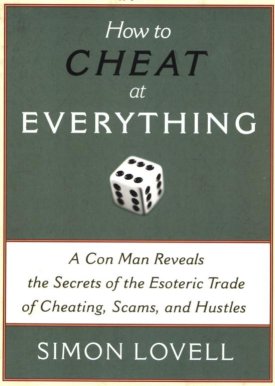

Check out Roadrace, the "Citizen Kane of Hot Wheels car chase videos," according to COOP! Simon Lovell's "How to Cheat at Everything: A Con Man Reveals the Secrets of the Esoteric Trade of Cheating, Scams and Hustles," is a veritable encyclopedia of cons, scams, tricks and rip-offs. Lovell is a magician by trade, and much of the book is given over to detailed sleight-of-hand HOWTOs for palming, greasing, fixing and cheating cards, dice, coins, and so on. Truth be told, this section bogged down a little for me -- unlike, say,

Simon Lovell's "How to Cheat at Everything: A Con Man Reveals the Secrets of the Esoteric Trade of Cheating, Scams and Hustles," is a veritable encyclopedia of cons, scams, tricks and rip-offs. Lovell is a magician by trade, and much of the book is given over to detailed sleight-of-hand HOWTOs for palming, greasing, fixing and cheating cards, dice, coins, and so on. Truth be told, this section bogged down a little for me -- unlike, say,

Entertaining video showing how Microsoft would re-designed Apple's elegant and understated packaging for the iPod.

Entertaining video showing how Microsoft would re-designed Apple's elegant and understated packaging for the iPod.

![[Susan Dudley]](http://online.wsj.com/public/resources/images/HC-GE708_Dudley_20051019035248.gif)

Recent Comments