Spontaneous eloquence seems to me a miracle,” confessed Vladimir Nabokov in 1962. He took up the point more personally in his foreword to Strong Opinions (1973): “I have never delivered to my audience one scrap of information not prepared in typescript beforehand … My hemmings and hawings over the telephone cause long-distance callers to switch from their native English to pathetic French.

“At parties, if I attempt to entertain people with a good story, I have to go back to every other sentence for oral erasures and inserts … nobody should ask me to submit to an interview … It has been tried at least twice in the old days, and once a recording machine was present, and when the tape was rerun and I had finished laughing, I knew that never in my life would I repeat that sort of performance.”

We sympathise. And most literary types, probably, would hope for inclusion somewhere or other on Nabokov’s sliding scale: “I think like a genius, I write like a distinguished author, and I speak like a child.”

Mr Hitchens isn’t like that. Christopher and His Kind runs the title of one of Isherwood’s famous memoirs. And yet this Christopher doesn’t have a kind. Everyone is unique – but Christopher is preternatural. And it may even be that he exactly inverts the Nabokovian paradigm. He thinks like a child (that is to say, his judgments are far more instinctive and moral-visceral than they seem, and are animated by a child’s eager apprehension of what feels just and true); he writes like a distinguished author; and he speaks like a genius.

As a result, Christopher is one of the most terrifying rhetoricians that the world has yet seen. Lenin used to boast that his objective, in debate, was not rebuttal and then refutation: it was the “destruction” of his interlocutor. This isn’t Christopher’s policy – but it is his practice. Towards the very end of the last century, all the greatest chessplayers, including Garry Kasparov, began to succumb to a computer (named Deep Blue); I had the opportunity to ask two grandmasters to describe the Deep Blue experience, and they both said: “It’s like a wall coming at you.” In argument, Christopher is that wall. The prototype of Deep Blue was known as Deep Thought. And there’s a case for calling Christopher Deep Speech. With his vast array of geohistorical references and precedents, he is almost Google-like; but Google (with, say, its 10 million “results” in 0.7 seconds) is something of an idiot savant, and Christopher’s search engine is much more finely tuned. In debate, no matter what the motion, I would back him against Cicero, against Demosthenes.

Whereas mere Earthlings get by with a mess of expletives, subordinate clauses, and finely turned tautologies, Christopher talks not only in complete sentences but also in complete paragraphs. Similarly, he is an utter stranger to what Diderot called l’esprit de l’escalier: the spirit of the staircase. This phrase is sometimes translated as “staircase wit” – far too limitingly, in my view, because l’esprit de l’escalier describes an entire stratum of one’s intellectual and emotional being. The door to the debating hall, or to the contentious drinks party, or indeed to the little flat containing the focus of amatory desire, has just been firmly closed; and now the belated eureka shapes itself on your lips. These lost chances, these unexercised potencies of persuasion, can haunt you for a lifetime – particularly, of course, when the staircase was the one that might have led to the bedroom.

As a young man, Christopher was conspicuously unpredatory in the sexual sphere (while also being conspicuously pan-affectionate: “I’ll just make a brief pass at everyone,” he would typically and truthfully promise a mixed gathering of 14 or 15 people, “and then I’ll be on my way”). I can’t say how it went, earlier on, with the boys; with the girls, though, Christopher was the one who needed to be persuaded. And I do know that in this area, if in absolutely no other, he was sometimes inveigled into submission.

The habit of saying the right thing at the right time tends to get relegated to the category of the pert riposte. But the put-down, the swift comeback, when quoted, gives a false sense of finality. So-and-so, as quick as a flash, said so-and-so – and that seems to be the end of it. Christopher’s most memorable rejoinders, I have found, linger, and reverberate, and eventually combine, as chess moves combine. One evening, close to 40 years ago, I said: “I know you despise all sports – but how about a game of chess?” Looking mildly puzzled and amused, he joined me over the 64 squares. Two things soon emerged. First, he showed no combative will, he offered no resistance (because this was play, you see, and earnest is all that really matters). Second, he showed an endearing disregard for common sense. This prompts a paradoxical thought.

There are many excellent commentators, in the US and the UK, who deploy far more rudimentary gumption than Christopher ever bothers with (we have a deservedly knighted columnist in London whom I always think of, with admiration, as Sir Common Sense). But it is hard to love common sense. And the salient fact about Christopher is that he is loved. What we love is fertile instability; what we love is the agitation of the unexpected. And Christopher always comes, as they say, from left field. He is not a plain speaker. He is not, I repeat, a plain man.

Over the years Christopher has spontaneously delivered many dozens of unforgettable lines. Here are four of them:

1. He was on TV for the second or third time in his life (if we exclude University Challenge), which takes us back to the mid-1970s and to Christopher’s mid-twenties. He and I were already close friends (and colleagues at the New Statesman); but I remember thinking that nobody so matinee-telegenic had the right to be so exceptionally quick-tongued on the screen. At a certain point in the exchange, Christopher came out with one of his political poeticisms, an ornate but intelligible definition of (I think) national sovereignty. His host – a fair old bruiser in his own right – paused, frowned, and said with scepticism and with helpless sincerity, “I can’t understand a word you’re saying.”

“I’m not in the least surprised,” said Christopher, and moved on.

The talk ran its course. But if this had been a frontier western, and not a chat show, the wounded man would have spent the rest of the segment leerily snapping the arrow in half and pushing its pointed end through his chest and out the other side.

2. Every novelist of his acquaintance is riveted by Christopher, not just qua friend but also qua novelist. I considered the retort I am about to quote (all four words of it) so epiphanically devastating that I put it in a novel – indeed, I put Christopher in a novel.Mutatis mutandis (and it is the novel itself that dictates the changes), Christopher “is” Nicholas Shackleton in The Pregnant Widow – though it really does matter, in this case, what the meaning of “is” is… The year was 1981. We were in a tiny Italian restaurant in west London, where we would soon be joined by our future first wives. Two elegant young men in waisted suits were unignorably and interminably fussing with the staff about rearranging the tables, to accommodate the large party they expected. It was an intensely class-conscious era (because the class system was dying); Christopher and I were candidly lower-middle bohemian, and the two young men were raffishly minor-gentry (they had the air of those who await, with epic stoicism, the deaths of elderly relatives). At length, one of them approached our table, and sank smoothly to his haunches, seeming to pout out through the fine strands of his fringe. The crouch, the fringe, the pout: these had clearly enjoyed many successes in the matter of bending others to his will. After a flirtatious pause he said, “You’re going to hate us for this.”

And Christopher said, “We hate you already.”

3. In the summer of 1986, in Cape Cod, and during subsequent summers, I used to play a set of tennis every other day with the historian Robert Jay Lifton. I was reading, and then re-reading, his latest and most celebrated book, The Nazi Doctors; so, on Monday, during changeovers, we would talk about the chapter “Sterilisation and the Nazi Biomedical Vision”; on Wednesday, “‘Wild Euthanasia’: The Doctors Take Over”; on Friday, “The Auschwitz Institution”; on Sunday, “Killing with Syringes: Phenol Injections”; and so on. One afternoon, Christopher, whose family was staying with mine on Horseleech Pond, was due to show up at the court, after a heavy lunch in nearby Wellfleet, to be introduced to Bob (and to be driven back to the pond-front house). He arrived, much gratified by having come so far on foot: three or four miles – one of the greatest physical feats of his adult life. It was set point. Bob served, approached the net, and wrongfootingly dispatched my attempted pass. Now Bob was, and is, 23 years my senior; and the score was 6-0. I could, I suppose, plead preoccupation: that summer I was wondering (with eerie detachment) whether I had it in me to write a novel that dealt with the Holocaust. Christopher knew about this, and he knew about my qualms.

Elatedly towelling himself down, Bob said, “You know, there are so few areas of transcendence left to us. Sports. Sex. Art … “

“Don’t forget the miseries of others,” said Christopher. “Don’t forget the languid contemplation of the miseries of others.”

I did write that novel. And I still wonder whether Christopher’s black, three-ply irony somehow emboldened me to attempt it. What remains true, to this day, to this hour, is that of all subjects (including sex and art), the one we most obsessively return to is theShoa, and its victims – those whom the wind of death has scattered.

4. In conclusion we move on to 1999, and by now Christopher and I have acquired new wives, and gained three additional children (making eight in all). It was mid-afternoon, in Long Island, and he and I hoped to indulge a dependable pleasure: we were in search of the most violent available film. In the end we approached a multiplex in Southampton (having been pitiably reduced to Wesley Snipes). I said, “No one’s recognised the Hitch for at least 10 minutes.”

Ten? Twenty minutes. Twenty-five. And the longer it goes on, the more pissed off I get. I keep thinking: What’s the matter with them? What can they feel, what can they care, what can they know, if they fail to recognise the Hitch?

An elderly American was sitting opposite the doors to the cinema, dressed in candy colours and awkwardly perched on a hydrant. With his trembling hands raised in an Italianate gesture, he said weakly, “Do you love us? Or do you hate us?”

This old party was not referring to humanity, or to the West. He meant America and Americans. Christopher said, “I beg your pardon?”

“Do you love us, or do you hate us?”

As Christopher pushed on through to the foyer, he said, not warmly, not coldly, but with perfect evenness, “It depends on how you behave.”

Does it depend on how others behave? Or does it depend, at least in part, on the loves and hates of the Hitch?

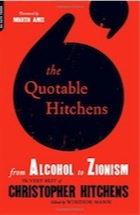

Christopher is bored by the epithet contrarian, which has been trailing him around for a quarter of a century. What he is, in any case, is an autocontrarian: he seeks, not only the most difficult position, but the most difficult position for Christopher Hitchens. Hardly anyone agrees with him on Iraq (yet hardly anyone is keen to debate him on it). We think also of his support for Ralph Nader, his collusion with the impeachment process of the loathed Bill Clinton (who, in Christopher’s new book, The Quotable Hitchens, occupies more space than any other subject), and his support for Bush-Cheney in 2004. Christopher often suffers for his isolations; this is widely sensed, and strongly contributes to his magnetism. He is in his own person the drama, as we watch the lithe contortions of a self-shackling Houdini. Could this be the crux of his charisma – that Christopher, ultimately, is locked in argument with the Hitch? Still, “contrarian” is looking shopworn. And if there must be an epithet, or what the press likes to call a (single-word) “narrative”, then I can suggest a refinement: Christopher is one of nature’s rebels. By which I mean that he has no automatic respect for anybody or anything.

The rebel is in fact a very rare type. In my whole life I have known only two others, both of them novelists (my father, up until the age of about 45; and my friend Will Self). This is the way to spot a rebel: they give no deference or even civility to their supposed superiors (that goes without saying); they also give no deference or even civility to their demonstrable inferiors. Thus Christopher, if need be, will be merciless to the prince, the president, and the pontiff; and, if need be, he will be merciless to the cabdriver (“Oh, you’re not going our way. Well turn your light off, all right? Because it’s fucking sickening the way you guys ply for trade”), to the publican (“You don’t give change for the phone? OK, I’m going to report you to the Camden Consumer Council”), and to the waiter (“Service is included, I see. But you’re saying it’s optional. Which? … What? Listen. If you’re so smart, why are you dealing them off the arm in a dump like this?”). Christopher’s everyday manners are beautiful (and wholly democratic); of course they are – because he knows that in manners begins morality. But each case is dealt with exclusively on its merits. This is the rebel’s way.

It is for the most part an invigorating and even a beguiling disposition, and makes Mr Average, or even Mr Above Average (whom we had better start calling Joe Laptop), seem underevolved. Most of us shakily preside over a chaos of vestigial prejudices and pieties, of semi-subliminal inhibitions, taboos and herd instincts, some of them ancient, some of them spryly contemporary (like moral relativism and the ardent xenophilia which, in Europe at least, always excludes Israelis). To speak and write without fear or favour (to hear no internal drumbeat): such voices are invaluable. On the other hand, as the rebel is well aware, compulsive insubordination risks the punishment of self-inflicted wounds.

Let us take an example from Christopher’s essays on literature . In the last decade Christopher has written three raucously hostile reviews – of Saul Bellow‘s Ravelstein(2000), John Updike‘s Terrorist (2006), and Philip Roth‘s Exit Ghost (2007). When I read them, I found myself muttering the piece of schoolmarm advice I have given Christopher in person, more than once: Don’t cheek your elders. The point being that, in these cases, respect is mandatory, because it has been earned, over many books and many years. Does anyone think that Saul Bellow, then aged 85, needed Christopher’s repeated reminders that the Bellovian powers were on the wane (and in fact, read with respect, Ravelstein is an exquisite swansong, full of integrity, beauty and dignity)? If you are a writer, then all the writers who have given you joy – as Christopher was given joy by Augie March and Humboldt’s Gift, for example, and by Updike’s The Coup, and by Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint – are among your honorary parents; and Christopher’s attacks were coldly unfilial. Here, disrespect becomes the vice that so insistently exercised Shakespeare: that of ingratitude. And all novelists know, with King Lear (who was thinking of his daughters), how sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless reader.

Art is freedom; and in art, as in life, there is no freedom without law. The foundational literary principle is decorum, which means something like the opposite of its dictionary definition: “behaviour in keeping with good taste and propriety” (i.e., submission to an ovine consensus). In literature, decorum means the concurrence of style and content – together with a third element, which I can only vaguely express as earning the right weight. It doesn’t matter what the style is, and it doesn’t matter what the content is; but the two must concur. If the essay is something of a literary art, which it clearly is, then the same law obtains.

Here are some indecorous quotes from the The Quotable Hitchens. “Ronald Reagan is doing to the country what he can no longer do to his wife.” On the Chaucerian summoner-pardoner Jerry Falwell: “If you gave Falwell an enema, he’d be buried in a matchbox.” On the political entrepreneur George Galloway: “Unkind nature, which could have made a perfectly good butt out of his face, has spoiled the whole effect by taking an asshole and studding it with ill-brushed fangs.” The critic DW Harding wrote a famous essay called “Regulated Hatred”. It was a study of Jane Austen. We grant that hatred is a stimulant; but it should not become an intoxicant.

The difficulty is seen at its starkest in Christopher’s baffling weakness for puns. This doesn’t much matter when the context is less than consequential (it merely grinds the reader to a temporary halt). But a pun can have no business in a serious proposition. Consider the following, from 2007: “In the very recent past, we have seen the Church of Rome befouled by its complicity with the unpardonable sin of child rape, or, as it might be phrased in Latin form, ‘no child’s behind left’.” Thus the ending of the sentence visits a riotous indecorum on its beginning. The great grammarian and usage-watcher Henry Fowler attacked the “assumption that puns are per se contemptible … Puns are good, bad, or indifferent … ” Actually, Fowler was wrong. “Puns are the lowest form of verbal facility,” Christopher elsewhere concedes. But puns are the result of an anti-facility: they offer disrespect to language, and all they manage to do is make words look stupid.

Now compare the above to the below – to the truly quotable Christopher. In his speech, it is the terse witticism that we remember; in his prose, what we thrill to is his magisterial expansiveness (the ideal anthology would run for several thousand pages, and would include whole chapters of his recent memoir, Hitch-22). The extracts that follow aren’t jokes or jibes. They are more like crystallisations – insights that lead the reader to a recurring question: If this is so obviously true, and it is, why did we have to wait for Christopher to point it out to us?

“There is, especially in the American media, a deep belief that insincerity is better than no sincerity at all.”

“One reason to be a decided antiracist is the plain fact that ‘race’ is a construct with no scientific validity. DNA can tell you who you are, but not what you are.”

“A melancholy lesson of advancing years is the realisation that you can’t make old friends.”

On gay marriage: “This is an argument about the socialisation of homosexuality, not the homosexualisation of society. It demonstrates the spread of conservatism, not radicalism, among gays.”

On Philip Larkin: “The stubborn persistence of chauvinism in our life and letters is or ought to be the proper subject for critical study, not the occasion for displays of shock.”

“[I]n America, your internationalism can and should be your patriotism.”

“It is only those who hope to transform human beings who end up by burning them, like the waste product of a failed experiment.”

“This has always been the central absurdity of ‘moral’, as opposed to ‘political’ censorship: If the stuff does indeed have a tendency to deprave and corrupt, why then the most depraved and corrupt person must be the censor who keeps a vigilant eye on it.”

And one could go on. Christopher’s dictum – “What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence” – has already entered the language. And so, I predict, will this: “A Holocaust denier is a Holocaust affirmer.” What justice, what finality. Like all Christopher’s best things, it has the simultaneous force of a proof and a law.

“Is nothing sacred?” he asks. “Of course not.” And no westerner, as Ronald Dworkin pointed out, “has the right not to be offended”. We accept Christopher’s errancies, his recklessnesses, because they are inseparable from his courage; and true valour, axiomatically, fails to recognise discretion. As the world knows, Christopher has recently made the passage from the land of the well to the land of the ill. One can say that he has done so without a visible flinch; and he has written about the process with unparalleled honesty and eloquence, and with the highest decorum. His many friends, and his innumerable admirers, have come to dread the tone of the “living obituary”. But if the story has to end too early, then its coda will contain a triumph.

Christopher’s personal devil is God, or rather organised religion, or rather the human “desire to worship and obey”. He comprehensively understands that the desire to worship, and all the rest of it, is a direct reaction to the unmanageability of the idea of death. “Religion,” wrote Larkin: “That vast moth-eaten musical brocade/ Created to pretend we never die …”

And there are other, unaffiliated intimations that the secular mind has now outgrown. “Life is a great surprise,” observed Nabokov (b. 1899). “I don’t see why death should not be an even greater one.” Or Bellow (b. 1915), in the words of Artur Sammler: “Is God only the gossip of the living? Then we watch these living speed like birds over the surface of a water, and one will dive or plunge but not come up again and never be seen any more … But then we have no proof that there is no depth under the surface. We cannot even say that our knowledge of death is shallow. There is no knowledge.”

Such thoughts still haunt us; but they no longer have the power to dilute the black ink of oblivion.

My dear Hitch: there has been much wild talk, among the believers, about your impending embrace of the sacred and the supernatural. This is of course insane. But I still hope to convert you, by sheer force of zealotry, to my own persuasion: agnosticism. In your seminal book, God Is Not Great, you put very little distance between the agnostic and the atheist; and what divides you and me (to quote Nabokov yet again) is a rut that any frog could straddle. “The measure of an education,” you write elsewhere, “is that you acquire some idea of the extent of your ignorance.” And that’s all that “agnosticism” really means: it is an acknowledgment of ignorance. Such a fractional shift (and I know you won’t make it) would seem to me consonant with your character – with your acceptance of inconsistencies and contradictions, with your intellectual romanticism, and with your love of life, which I have come to regard as superior to my own.

The atheistic position merits an adjective that no one would dream of applying to you: it is lenten. And agnosticism, I respectfully suggest, is a slightly more logical and decorous response to our situation – to the indecipherable grandeur of what is now being (hesitantly) called the multiverse. The science of cosmology is an awesome construct, while remaining embarrassingly incomplete and approximate; and over the last 30 years it has garnered little but a series of humiliations. So when I hear a man declare himself to be an atheist, I sometimes think of the enterprising termite who, while continuing to go about his tasks, declares himself to be an individualist. It cannot be altogether frivolous or wishful to talk of a “higher intelligence” – because the cosmos is itself a higher intelligence, in the simple sense that we do not and cannot understand it.

Anyway, we do know what is going to happen to you, and to everyone else who will ever live on this planet. Your corporeal existence, O Hitch, derives from the elements released by supernovae, by exploding stars. Stellar fire was your womb, and stellar fire will be your grave: a just course for one who has always blazed so very brightly. The parent star, that steady-state H-bomb we call the sun, will eventually turn from yellow dwarf to red giant, and will swell out to consume what is left of us, about six billion years from now.

Recent Comments