Among the defining attributes of now are ever tinier gadgets, ever shorter attention spans, and the privileging of marketplace values above all. Life is manically parceled into financial quarters, three-minute YouTube videos, 140-character tweets. In my pocket is a phone/computer/camera/video recorder/TV/stereo system half the size of a pack of Marlboros. And what about pursuing knowledge purely for its own sake, without any real thought of, um, monetizing it? Cute.

And so in our hyper-capitalist flibbertigibbet day and age, the new Large Hadron Collider, buried about 330 feet beneath the Swiss-French border, near Geneva, is a bizarre outlier.

The L.H.C., which operates under the auspices of the European Organization for Nuclear Research, known by its French acronym, cern, is an almost unimaginably long-term project. It was conceived a quarter-century ago, was given the green light in 1994, and has been under construction for the last 13 years, the product of tens of millions of man-hours. It’s also gargantuan: a circular tunnel 17 miles around, punctuated by shopping-mall-size subterranean caverns and fitted out with more than $9 billion worth of steel and pipe and cable more reminiscent of Jules Verne than Steve Jobs.

The believe-it-or-not superlatives are so extreme and Tom Swiftian they make you smile. The L.H.C. is not merely the world’s largest particle accelerator but the largest machine ever built. At the center of just one of the four main experimental stations installed around its circumference, and not even the biggest of the four, is a magnet that generates a magnetic field 100,000 times as strong as Earth’s. And because the super-conducting, super-colliding guts of the collider must be cooled by 120 tons of liquid helium, inside the machine it’s one degree colder than outer space, thus making the L.H.C. the coldest place in the universe.

If all has gone according to plan, the physicists at cern by late November will have flipped a switch, and proton beams in each of two pipes will have started shooting around the ring, one beam clockwise and the other counterclockwise, at an energy level of 3.5 trillion electron volts, several times that of the current most-powerful-particle-accelerator-ever-built. And then, any day now, the L.H.C.’s proton streams will be forced to begin colliding head on, at a combined energy of seven trillion electron volts, producing up to 800 million collisions per second.

So many years, so much effort, so much money and matériel, so much energy and cutting-edge ingenuity. And yet the wizards at the controls aren’t really out to produce anything practical, or solve any urgent human problem. Rather, the L.H.C. is, essentially, a super-microscope that will use the largest energies ever generated to examine trillionth-of-a-millimeter bits of matter and record evanescent blinks of energy that last for only trillionths of a trillionth of a second. It’s also a kind of time machine, in the sense that it will reproduce the conditions that prevailed 14 billion years ago, giving scientists a look at the universe as it existed a trillionth of a second after the big bang. The goal—and it’s a hope, a dream, a set of strong suspicions, rather than a certainty—is to achieve a deeper, better, truer understanding of the fundamental structure and nature of existence.

In other words, it’s one of the most awesome scientific enterprises of all time, even though it looks like a monumental folly. Or else, possibly, the reverse.

The Quench

When the proton beams start shooting around, it will in fact be for the second time. The On buttons of the new super-collider were first punched on September 10, 2008, and for a while everything was going extraordinarily well. The start-up had been preceded by some well-publicized hysteria on the fringes, with alarmists worrying that the L.H.C. would create a black hole that could swallow the earth. (The fear is unfounded.) There was also a cern subplot in Dan Brown’s Angels and Demons, in which Illuminati steal anti-matter from the L.H.C. in order to evaporate the Vatican. (Also not a concern—it would take an impossible amount of time and energy to produce enough anti-matter to make a bomb.) On September 10, the physicists at cern could not have been more pleased. Within 50 minutes of the start-up the proton beams were firing perfectly. Plus, says Dave Barney, a British physicist who has devoted his professional life to the collider, “the world hadn’t been destroyed. So that was nice.”

But then, Barney notes, “the 19th happened.” By September 19, a Friday, the collider had been humming along for nine days, and proton collisions were imminent. In one of its eight two-mile-long sectors, the power had already been raised almost to the maximum with no problems, while seven of the eight sectors were “commissioned,” or fully activated. The last to go was the sector beneath the French villages of Crozet and Échenevex, at the foot of the Jura Mountains. Around noon the power there was cranked up past 5 trillion electron volts, toward 5.5.

The tunnel of the L.H.C. is a 12-foot-wide concrete tube, like a very large sewer pipe but lit and air-conditioned for the technicians who must access the machinery. The accelerator consists of 1,232 cylinders, each of them 50 feet long and 2 feet thick, strung through the tunnel like a 17-mile chain of 35-ton sausage links laid in a circle. The proton beams are fired through three-inch pipes embedded in the center of the sausages. Surrounding those pipes inside the giant sausages are powerful electromagnets, which make the protons travel in their great circles at nearly the speed of light. And surrounding each of the magnets—the sausage casing—is a jacket of liquid helium to cool the super-conducting cables. When they’re turned on, the force inside, pushing out against the super-hardened steel container, is equal to the power of a 747 taking off.

The big magnetic sausages are called dipoles, and the bundled cables connecting each one to its end-to-end neighbor are packed inside copper casings the size of a cigarette lighter. Each casing is filled with solder to make the connection solid. As it happened, that was the source of the problem: one of the copper casings on one of the dipoles had not been properly soldered. And so, around midday on September 19, 2008, the connection “quenched”—which means a super-conducting cable suddenly lost its super-conductivity, turning into an ordinarily conductive wire that couldn’t take the 11,000 amps of electricity.

Sparks erupted. An intense electrical arc began burning a hole in the dipole’s steel jacket. Pressurized helium turned from liquid to gas and blasted into the tunnel, creating a huge pressure wave. In a domino-like chain reaction, 35-ton dipoles were jerking and smashing against other 35-ton dipoles, some blown two feet off their moorings.

The main damage was done within 20 seconds. It was all over a half-minute after that. Ten of the million-dollar dipoles were wrecked and smoldering. Twenty-nine more were damaged. The destruction extended for more than 2,000 feet, and smoke and soot billowed through the tunnel. In the vicinity of the accident the air had been instantly supercooled by the tons of escaping helium—which meant that several hundred feet underground, sealed off from skies and weather, snow began to fall. “Some say the world will end in fire / Some say in ice,” wrote Robert Frost, but in this sector of the Large Hadron Collider, the showstopping spectacle involved both at once.

Up on the surface, in the control rooms, there was in fact no sound, no bump, no rumble. No sirens or Klaxons went off. But in the main control room, someone noticed that green tabs on one of the 300 computer monitors had suddenly turned red: the emergency Stop buttons in the tunnel had been hit. No one had been down there to hit them—the tremendous pressure wave of escaping helium had fortuitously done the job.

More monitors started turning red. “The beam is gone,” Alick Macpherson, a particle physicist from New Zealand, said to the scientists around him. In many languages at once people quietly muttered “Fuck” and “Shit.”

A Theory of Everything

At cern, people generally refer to the catastrophe simply as “September 19.” And they can’t help but think about it as they get ready, more than a year later, to try again. For particle physics, the Large Hadron Collider is pretty much the whole ball game. Its 26-year-old predecessor, the U.S. government’s Tevatron, at Fermilab, outside Chicago—an accelerator less than one-fourth as big and one-seventh as powerful as the L.H.C.—is supposed to be decommissioned at the end of 2010. If this new collider doesn’t produce groundbreaking discoveries, particle physics will have reached a dead end for a generation or more. The theorists would keep theorizing. But without hard experimental data pouring out of the L.H.C., says Jim Virdee, a Kenyan-born British-Indian physicist with the L.H.C., then “particle physics, the whole thing, becomes metaphysics.”

The Large Hadron Collider is the circular structure itself. Four main experiments lie along the path.

To the rest of us, the refinements of knowledge the physicists are after seem supremely abstruse—so beyond ordinary understanding that they might as well be metaphysics, or computer-generated poetry. The mission, for instance, of alice (short for “A Large Ion Collider Experiment”), one of the four experiments at the L.H.C., is “to study vector meson resonances, charm and beauty through the measurement of leptonic observables.” And how many angels can dance on the head of a pin?

The history of particle physics is like a Russian nested doll, with each new generation of physicists prying open the next, smaller doll. First, a century ago, they opened up the atom and found the most obvious particles, the nucleus and its orbiting electrons. Then they opened up the nucleus and found the protons and neutrons. Inside these they found quarks and gluons. And so on. The buzzing energy “strings” hypothesized by superstring theory for the past couple of decades—and never observed in any experiment so far—may be the last and tiniest of the nesting dolls, the most fundamental components of the universe.

One of the paradoxes of physics is that as knowledge has dramatically grown—thanks to particle physicists opening the smaller and smaller dolls, and to astrophysicists measuring the distances and movements and energies of stars—so has our awareness of the vastness of our ignorance. That is, physicists now say that all the visible matter in the universe—galaxies, stars, asteroids, comets, gases, planets, you, this magazine—amounts to just 4 percent of the total, and that the remaining 96 percent consists of “dark energy” (about three quarters) and “dark matter” (about one quarter). But those names are really just black-box placeholders (like “God”). The only evidence for their existence is entirely indirect.

That paradox—knowledge increasing as uncertainty and incompleteness also increase—is problematic when it comes to what particle physicists call their Standard Model. As the name suggests, the Standard Model, developed over the last half-century, is meant to be the definitive diagram of that nested doll. The model’s premises and predictions have been confirmed again and again by experiments at cern and elsewhere. It seems to explain how all the particles that make up visible matter stick together. That’s the good news. The bad news is that it doesn’t say anything about gravity or dark matter or dark energy. James Gillies, an Oxford-educated particle physicist (and cern’s P.R. director), puts it this way: the Standard Model is what “quantum physics has been all about testing since the 1970s, and proving. But it can’t be right.” What he really means is: It can’t be all there is.

With the Large Hadron Collider, the physicists think they will find the last remaining puzzle piece that confirms the Standard Model and, even better, get some glimpses of a vast and tantalizing terra incognita. They hope to be able to move beyond the Standard Model the way Einstein moved beyond Newton with his theories of relativity, not by disproving Newtonian physics wholesale but by correcting and expanding upon it.

In other words, the L.H.C. is a machine that will really justify itself only if it enables paradigm-shifting breakthroughs. “I hope there will be many eureka moments,” says Fabiola Gianotti, a physicist from Milan who heads the L.H.C.’s big atlas experiment. (That strenuously reverse-engineered acronym stands for “A Toroidal L.h.c. ApparatuS.”) “Whatever else,” says John Ellis, a British theoretical physicist at cern, “we should get Higgs and supersymmetry. Higgs is the bread and butter. That’s our core business.” The Higgs boson, named after the British physicist Peter Higgs, who predicted its existence in the 1960s, is the one particle predicted by the Standard Model that hasn’t yet been found. And it’s not just some stray, inconsequential leftover piece but a keystone of the whole structure: the Higgs field, associated with Higgs bosons, is imagined to be a kind of subatomic “molasses” that imparts mass to other particles passing through it. The consensus at cern is that it will probably take a few years to find the Higgs. (A pair of physicists have suggested, winsomely and implausibly, that last year’s snafu was the result of some entity from the future attempting to prevent the L.H.C. from creating Higgs bosons—somehow and for some reason committing sabotage-by-time-travel, Terminator-style.)

But then there’s the important question of how big the Higgs boson turns out to be. If it comes in at a certain size, that would mean that the universe is stable and not doomed to decay—which Ellis calls the “massive conceivable disaster scenario.”

But wouldn’t such a finding—stability! a never-ending universe!—be a happy outcome? “It’s great for the universe,” Ellis concedes, “but disastrous for theoretical physicists.” Professor Higgs, who is now 80, agrees. “If you find the Higgs and nothing else,” he told Gillies recently, that would be the worst possible result, “because then we have a complete Standard Model—which we know is wrong in fundamental ways.” It would be as if we’d known for the last century that Newton’s picture of the universe was flawed and incomplete, but never had Einstein or his followers to move us along to a bigger, more correct picture. On the other hand, Ellis says, “it would be exciting if we proved Higgs didn’t exist. I’d love to be shocked and surprised.” That is, he’d rather have the last several decades of conventional wisdom in physics upended than have the next several decades rendered inconclusive, impotent, and boring.

Apart from discovering (or not discovering) the Higgs, the best odds for a thrilling eureka moment from the L.H.C. would be on discovering that supersymmetry exists. “We have a religion,” an American physicist and cern lifer named Steven Goldfarb confessed one day over lunch, “and that’s symmetry.” As yin is twinned with yang and Christ with Antichrist, so does matter have its equal and opposite anti-matter, and they destroy each other on contact—so that, according to the guiding principle of symmetry, at the moment of the big bang, all the matter and anti-matter should have canceled themselves out, leaving nothing behind. Not only did that not happen—we are among the evidence that it didn’t—but 14 billion years later there is a lot more matter than anti-matter in the universe. Something has to explain that mysterious imbalance, and the betting is that it’s supersymmetry, the idea that for every known particle there’s an as-yet-undetected “superpartner”—and that dark matter consists of those superpartners. There’s a very good chance that the proton collisions at the L.H.C. will create some of those primordial bits—maybe next year, says Jim Virdee, who runs the collider’s C.M.S. experiment, “if nature is kind.” (C.M.S. stands for “Compact Muon Solenoid”—don’t ask.) If that happens, in one stroke “we’ve figured out 25 percent of the universe,” says Gillies.

The L.H.C. discoveries that would make regular people stand up and pay attention, though, are somewhat longer shots. After the Higgs is found (or not) and supersymmetrical particles of dark matter produced (or not), Ellis says, “we can find extra dimensions, black holes, all sorts of weird and wonderful things.”

Wait a second: black holes? Yes, though not the kind that alarmists have been screaming about. The doomsday chatter reached critical mass last year when a high-school teacher and botanical-garden manager in Hawaii named Walter Wagner filed a federal lawsuit to prevent the L.H.C. from operating, on the grounds that it might create a massive, world-destroying black hole. This has been a longtime side career for Wagner, who had also tried to stop the Brookhaven National Laboratory from turning on its own, smaller accelerator. But this time, with the help of cable news channels and the Web, he had a much bigger platform, and mainstream media consistently took the apocalypse possibility seriously. The federal lawsuit was dismissed, but it was left to The Daily Show to definitively call a spade a spade and a loon a loon. Interviewed by the show’s John Oliver last spring, Wagner insisted, moronically, that the chance of the L.H.C. destroying the earth was 50-50, since it will either happen or it won’t.

The detector for another collider experiment—this one beneath the Swiss town of Meyrin—is known as alice. Particles destined for collisions travel inside the blue pipe.

The kind of black holes that Ellis has in mind are harmless ones, microscopic and incredibly short-lived, although produced, if they are produced, by the thousands or millions a year. “That will take time,” says cern’s director general, Rolf-Dieter Heuer, and probably only when the L.H.C. is running at maximum power. But if micro black holes do appear, Ellis says, it would be “fantastically exciting,” since they would imply the existence of additional spatial dimensions beyond the three we know. Finding new dimensions would be exciting for us civilians, but, for physicists, it may hold the key to creating, at long last, a unified physics that makes sense of both the tiny-scale forces that hold atoms together and the gravity that pulls on everything we can actually see. Some physicists think the reason gravity is comparatively weak is that it gets diluted as it courses in and out of other, unseen dimensions. If extra dimensions are indeed found at the L.H.C., then string theory—already the leading candidate to become the unified Theory of Everything—would suddenly seem a lot more real.

Maria Spiropulu, a Greek-born Cal Tech–affiliated physicist who wears scuffed jeans and sneakers without laces (and used to be in a band called Drug Sniffing Dogs), radiates confidence about imminent breakthroughs. When I say that her experiment, C.M.S., is “simulating the conditions” at the beginning of the universe, she emphatically corrects me. “No—we’re re-creating those conditions. We will find out the fundamental nature of how the universe is created.” And even the relatively tentative, low-key Gianotti has little doubt that what they’re about to discover will rank with “Copernicus, Einstein, quantum mechanics. I do expect a revolution.”

Republic of Wizards

The quest is as profound as it gets: what are we (and everything else in the universe) made of, what was it like at the beginning of time, and how does it all actually work? The fact that the L.H.C. is a magnificently expensive gamble that has no short-term payoff is what makes it noble and stirring.

Just before my journey to Geneva, I’d happened to read Richard Holmes’s new book, The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science, a history of a group of scientist-adventurers of the late 18th and early 19th centuries who discovered comets and Uranus and Tahiti and hot-air ballooning. As I wandered the subterranean bowels of the L.H.C. and talked with a score of the physicists who have devoted their careers to it, the beauty and terror and romance were everywhere. Just as George III was persuaded by the self-taught astronomer William Herschel 228 years ago to spend an enormous royal sum to build what was then the world’s largest, most powerful telescope, the physicists at cern have their generous patrons in governments all over the world.

The L.H.C. is the largest machine and, after the Manhattan Project, the most elaborate scientific enterprise of all time, but it’s also, to my postmodern eyes, the largest art project ever built, as well as a quasi-religious undertaking. All sorts of people make pilgrimages to the L.H.C. simply in order to be awestruck, the way they visit Stonehenge or Machu Picchu or the pyramids. On one of the days I toured the L.H.C., I was joined by the art collector Francesca von Habsburg and her 12-year-old son, Archduke Ferdinand; the Icelandic pop musician Einar Örn Benediktsson, formerly of the Sugarcubes; and ex–Sex Pistol Glen Matlock. A quarter-century in the making, the L.H.C. is a 21st-century cathedral of science, where thousands of passionately devoted, hardworking physicists—monks by any other name—have gathered to experience epiphany and revelation, and continue writing Genesis 2.0.

Many of the scientists, not surprisingly, bridle at the suggestion that what they’re doing is gloriously impractical or akin, even in the best sense, to the uselessness of art or religion. But Fabiola Gianotti’s education was focused on music and literature until she took up physics in college, and she totally gets the art part. “We have dreams,” she says. “It’s like art. Is art useless? Yes and no. The concepts [of particle physics] are so beautiful in their simplicity. And they answer the most fundamental questions. Physics and art are two forms of the same wish of human intuition, to understand nature.”

About half the particle physicists on earth are on the L.H.C. team, some 7,200 in all. About 1,500 of them are full-time, working and living around the collider. (One researcher, a young Frenchman of Algerian origin, was arrested in October by French authorities, accused of contacting al-Qaeda.) Although the United States isn’t officially part of the 20-country, all-European cern consortium, more of the scientists on site are American than any other nationality. (The U.S. government also chipped in $542 million to build the L.H.C. and its detectors.) As a particle physicist, says Rolf-Dieter Heuer, “you have to be flexible. You have to go where the accelerator is.” Now 61, he spent 14 years working on the L.H.C.’s predecessor, the Large Electron Positron collider, which occupied the same 17-mile tunnel before it shut down, in 2000. After a decade back home in Germany, he returned to cern to start running the place. “They pulled me back in. You don’t say no.”

Physically, cern is charmingly tatty. It was founded in the 1950s, and many of the original office and lab buildings—unfabulous International Style low-rises from the time when particle accelerators were known as atom smashers—are still in use. cern looks and feels like a cross between an office–cum–industrial park and a university campus—but, except for the casual modern wardrobe (jeans, shorts, no ties), a university in the 1950s or 60s, with few women or people of color, and plenty of cigarette smoking. Because the physicists come from dozens of countries, the lingua franca among the scientists in this French-speaking patch of Europe is English. The streets are named after giants of the past—Route A. Einstein, Route N. Bohr, Route M. Curie—but the big science pursued at cern is of a very 21st-century kind, less a habitat for solitary geniuses than a well-organized hive of thousands of smart people each doing his or her bit for the collective mission.

I was repeatedly reminded of Arthur C. Clarke’s remark that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” cern may be the closest thing real life has to Hogwarts, an institution where arcane arts amounting to sorcery are pursued by a cultish guild of masters and their young protégés. (Rolf-Dieter Heuer, lanky and white-bearded, witty and wise and a bit stern, makes a fine Dumbledore.) I am a longtime subscriber to Scientific American, follow science pretty closely, and have the journalist’s ability to fake fluency in all kinds of subjects, but on my last afternoon at cern I was exposed as a total Muggle among the wizards. Stephen Hawking arrived to deliver a lecture called “Spontaneous Creation of the Universe” to a standing-room-only audience. For 25 of his 30 minutes I simply had no clue at all what he was saying, none, and it wasn’t because of his electronic voice synthesizer. I realized that the physicists with whom I’d been speaking all week had been radically dumbing down their explanations so that I, a functional fifth-grader, might achieve some tiny glimmer of understanding.

Another strange thing about the place is the way it’s run. Unlike a college or think tank, at the L.H.C. everyone’s work has the same unambiguous focus: building and running a collider on an unprecedented scale, which involves designing and ordering and assembling millions of incredibly precise, one-off parts from all over the world. You’d think it would need to be governed like a brutally efficient corporate or military enterprise, with strict, top-down command and control. But, amazingly, it’s more or less a direct democracy, maybe the most successful since ancient Athens.

The venerable Gargamelle bubble chamber (1973), the particle detector used to make the first great discovery at cern. cern’s director general, Rolf-Dieter Heuer (second from left), is flanked by physicists John Ellis, Steve Myers, and Fabiola Gianotti.

“The model is: Everyone’s equal,” says Gillies. “It’s management by consensus.” The leaders and deputy leaders of each of the experimental teams are elected by fellow scientists to a fixed term. Team leaders are called “spokespeople.” Heuer says governance is a sui generis crossbreed of a private company and a university, with “the chaos of hundreds of university professors. The top guy”—meaning himself, and the heads of each of the L.H.C.’s experiments—“can only convince the other guys to do what he wants them to do. That I find fascinating. Even with a democratic approach, you need to know where you want to go” and provide “clear line management.” So, I suggest, his job is creating for all these independent-minded brainiacs the illusion of democracy? “‘Illusion’ is too strong, but … ” He laughs. “Of course, you are right to some extent.”

Collisions by Christmas

During the past year, the efforts of everyone have been bent toward a single task: fixing the collider. The repairs have cost nearly $40 million. The pipes have been cleared of soot. All 9,560 solders have been tested. Thirty of the damaged dipoles have been replaced with the entire stock of spares, 600 more have been fitted with new helium-release valves, and all the dipoles have been anchored to the floor more securely. The machinery is now supposed to withstand an accident 20 times the size of the previous worst-case scenario.

When I visited this past fall, the hard hats were finishing up, replacing components and checking cables. The astonishing physical scale of the space underground makes visitors gasp and grin and gaze openmouthed. The first vertiginous moments of wonder come at the lips of the concrete shafts into which gantry cranes have lowered giant pieces of machinery, piece by Brobdingnagian piece, into the subterranean caverns. At the edge of one 33-story shaft, a tennis-court-size rectangular opening next to a circular one, I had a déjà vu moment: the shaft is a scaled-up, super-duper-size version of Michael Heizer’s (enormous) artwork North, East, South, West, at the Dia:Beacon museum in New York.

The heart of each of the four experiments is a detector, inside which the proton collisions will take place and the resulting splashes of particles will be tracked. The detector for the C.M.S. experiment weighs 28 million pounds, the heaviest instrument ever constructed, heavier than the Eiffel Tower. Its centerpiece magnet alone weighs more than four million pounds and took 10 hours to lower 300 feet, touching the floor within one-twentieth of an inch of its intended place, then nudged to within one-hundredth of an inch. The machine for another main experiment, atlas, is lighter, but in volume it’s the largest scientific instrument in history, 150 feet long and 80 feet high.

Passing through the electronic security gates (door opens, enter cage, door closes, stand in yellow-painted square, look at iris-scanning ID device, second door opens, proceed), you begin to feel as if you’ve stepped into a movie. The full-color video-surveillance monitors and illuminated signs—danger: magnetic field and in case of alarm do not go down—seem like slightly stagy props, as do the French and Swiss flags at every point where the 17-mile tunnel crosses the border.

Down in the caverns, the experience becomes a full-bore cinematic pastiche. I was reduced to monosyllabic Keanu Reevesian awe, repeatedly saying “Whoa” as I encountered the sci-fi vistas—Ernst Blofeld’s volcano fortress crossed with a Star Wars rebel hangar crossed with Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory and Zion from The Matrix Reloaded.

And now, once more, it’s showtime. When the L.H.C. starts running again, I wondered, where will the zillions of protons in the beam actually come from? Dave Barney took me for a long walk, down alleys, through parking lots, and into one of cern’s nondescript 1950s buildings. “There,” he said, pointing at a red cylinder that looked like the fire extinguisher I keep in my kitchen. He told me it’s a one-liter tank of hydrogen. I was flabbergasted. A $9 billion, 17-mile-long, unfathomably complex contraption meant to unlock the mysteries of the universe … and that’s it, the source, the wellspring? Yes, he said. “That will feed the L.H.C. forever with protons of hydrogen. It’s all fed from that tiny gas bottle.”

Atom by atom, the electrons will be stripped from each hydrogen nucleus to create free protons, which will then be beamed into a series of four pre-accelerators of increasing size, one after another, in a kind of loop-de-loop, each pre-accelerator powering the beam up by a factor of 10 or 20 or 30, finally up to 3.5 and—sometime early in the new year—7 trillion electron volts. As the energy increases, the beams will narrow, be steered and focused from the main control room, and then be “injected” into the collider. (I finally indulged my inner 12-year-old, asking one of the top managers of the accelerator team, Paolo Fessia, if I’d feel a proton beam if it were pointed at me. “I’ve never thought about that,” he replied. But he said it would bore a quarter-mile-long hole through any material.) The excitement will peak when the protons start colliding and the machine thereby achieves, in the lovely term of art, “luminosity.” According to Heuer, “We should have collisions before Christmas.” He’s amused enough by his alliterative holiday promise to repeat it: “Collisions by Christmas!”

The resulting gushers of raw data will be winnowed in real time, both automatically by software algorithms and on the fly by human number crunchers. The distilled one-tenth of 1 percent of the data—the equivalent of 55,000 CDs’ worth of information each day—will be sluiced out to 160 different academic institutions. To be sure, says Gillies, “it wouldn’t be possible without the Web.” How fortunate, then, that at the very moment the L.H.C. was being dreamed up at cern, 20 years ago, so was the World Wide Web, by a computer programmer at cern named Tim Berners-Lee. The moral: cern-style science for science’s sake is not to be pooh-poohed, even when it seems impossibly arcane.

The excitement among the scientists at cern is palpable. They are explorers who have prepared for decades and are finally about to set off for uncharted regions. They will work around the clock. “This machine will be giving good science for years,” Heuer says, actually rubbing his hands. Just the other day, Karl Gill, a British physicist on the C.M.S. experiment, started preparing his family for the new rhythms of his life. “I said to my wife, ‘I’ll have to work shifts.’ She asked, ‘For how long?’” He smiled a little sheepishly. “Oh,” he told her, “for 10 or 15 years. For the rest of my life.”

Kurt Andersen is a Vanity Fair contributing editor.

Due to a formatting error, the online version of this story misidentified several of the L.H.C.’s experiments. These discrepancies have been corrected.

Copyright 2010. Vanity Fair. All Rights Reserved.

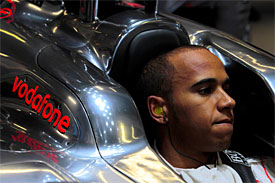

Lewis Hamilton insists he has drawn a line under the Italian Grand Prix, saying he has moved on from the disappointment to focus on the next race in Singapore.

Lewis Hamilton insists he has drawn a line under the Italian Grand Prix, saying he has moved on from the disappointment to focus on the next race in Singapore.

Recent Comments