January 27, 2007

-

January 27, 2007

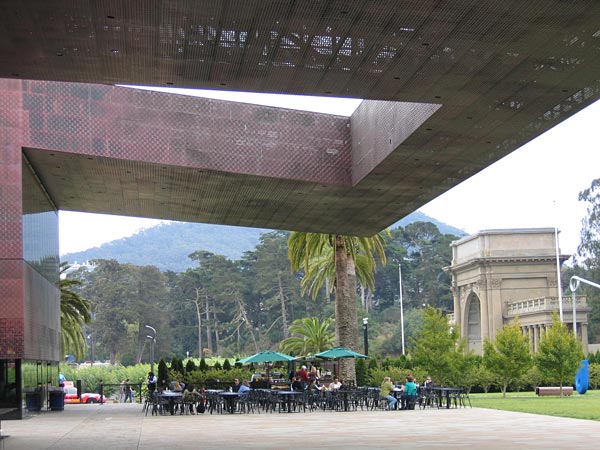

- The new de Young museum in San Francisco

..>

Image courtesy the author.

The new de Young museum in San Francisco, which opened in 2005, replaces a Spanish-style building that had been insensitively “modernized” in 1949, fatally weakened by the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, and finally demolished in 2003. Despite billing itself as a “museum of the 21st century,” the new building has many of the hallmarks of a 19th-century art gallery: skylights, separate wings for different collections, landscaped courtyards, and a grand staircase. What is decidedly unconventional, in this age of extrovert cultural institutions, is the exterior appearance, which, from a distance, is slightly forbidding, uncommunicative, almost grim.

..>

Image courtesy the author.

..>

..>

..>

Image courtesy the author.

..>

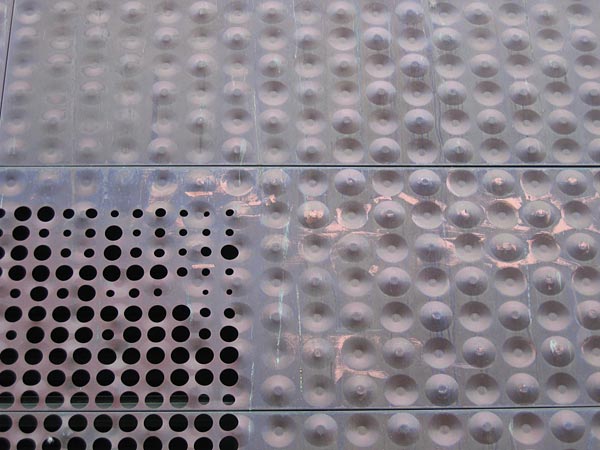

Unusual exterior cladding is something of a trademark of the primary design architects, the Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, who have previously used skins of twisted copper strips, printed acrylic, and silk-screened glass and concrete. The walls of the de Young are paper-thin copper panels, both dimpled and perforated. The dimples—concave and convex—create changing textures, while the perforations, which vary in size and density, emphasize the thinness and create the effect of a scrim. Like the exteriors of many recent buildings (Zaha Hadid’s Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, Daniel Libeskind’s Denver Art Museum, Herzog & de Meuron’s own addition to the Walker Art Gallery), the walls neither reveal structure nor express inner organization. Instead, the patterns are purely ornamental, which makes them curiously similar in function to the moldings and decorations on the exteriors of classical buildings. The trend suggests just how far from its Modernist roots the current

Image courtesy the author.

- Illegal Sublets Put Private Eyes on the Case

Marko Georgiev for The New York Times

Marko Georgiev for The New York TimesBill Golodner, whose work includes checking whether people are illegally subletting rent-regulated apartments, at work in Queens.

Illegal Sublets Put Private Eyes on the Case

The house was one of those stucco numbers that grow in the suburbs like crab grass. The woman in question was a cagey brunette suspected of chiseling her landlord. She had a rent-regulated apartment in Manhattan that she seemed to be subletting illegally for twice what she was paying, while sleeping in the stucco house just outside the city.

Bill Golodner idled his sport utility vehicle beside the curb a few doors down. He clipped a surveillance camera to the steering wheel and brought the house into focus. He ran a rough paw over his shaved head, switched on a camera concealed behind the third buttonhole of his dress shirt, then slipped out into the chill morning, heading for the front door.

Philip Marlowe, if he were around, might be doing rent-fraud cases, too.

These are busy times for private investigators in the real estate racket in New York City. Market-rate rents are in the exosphere. Denizens of the city’s 1.1 million rent-regulated apartments have dug in, and landlords are shelling out serious money in search of grounds to dislodge rent-law violators and get a chance to push up rents when an apartment turns over to a new tenant.

At the confluence of those crosswinds, a private eye can flourish. Investigators like Mr. Golodner sweep up whatever incriminating evidence can be used by building owners and their lawyers to show scofflaw tenants the wisdom of, say, relocation.

Mr. Golodner and his partner, Bruce Frankel, both former New York City police detectives, say their firm has handled close to 500 real estate cases in the past year. They mine public records, plumb the depths of the World Wide Web, plant hidden cameras — trawling for proof of illegal subletting, income-limit violations and the improper use of apartments for businesses, even prostitution and drug dealing.

“Everybody thinks landlords are bad and we can steal from them,” said Mr. Frankel, a helicopter door gunner in Vietnam who later worked in the garment center and can still spot a tailor-made suit by the sleeve buttons alone. “We live in a life of double standards. We have all these great people who go to work, donate to charities, talk about how the war is horrible — but everybody still thinks it’s O.K. to have the Robin Hood mentality.”

Take the tenant who seemed to be allowing her Manhattan apartment to be used for illicit business. The owner of the building answered an ad for what Mr. Frankel and Mr. Golodner call a massage. Unexpectedly, he found himself in a building he owned. When Mr. Frankel and Mr. Golodner investigated, they say the found the tenant of record was paying $800 a month but living in Westchester County, while collecting $2,700 a month from the woman in the apartment selling her services.

Another woman claimed to be living in her rent-regulated West Village apartment, for which she paid about $1,500 a month, less than half the market rate. Mr. Frankel and Mr. Golodner say they found her in South Dakota, after her address surfaced in a public-records search because she had applied for a license to work in the gambling industry. They say they interviewed the lawyer who had helped her buy a house in the Badlands; they believe she was planning to hand over the apartment to her son, who was not yet living in New York.

Another private investigator, Nick Himonidis, founder of NGH Associates in Roslyn Heights, N.Y., recalled a case in which a tenant was operating an architectural office out of a rent-regulated apartment: three architects, support staff, cleaning crews. Two investigators from Mr. Himonidis’s office made an appointment, talked to the architects and asked for a tour of the office. They captured the whole thing on hidden cameras.

“As a percentage of our business, our work for landlords as clients has probably gone from 5 percent to closer to 20 percent in the last 24 months,” said Mr. Himonidis, who believes the rise in rents has made an owner more likely to call in an investigator. “It simply might not have made economic sense 5 or 10 years ago. And now it does.”

Samuel J. Himmelstein, a Manhattan lawyer who has represented tenants for 28 years, says the number of cases filed by landlords against tenants jumped in the late 1990s after the law was changed to make it easier for apartments to be deregulated once they become vacant. He said surveillance video tapes are increasingly the preferred standard of proof that a tenant is not living in his apartment — or that someone else is.

Mr. Himmelstein said: “I get a lot of clients who get these suspicious phone calls. Someone will say, ‘We have a case of wine someone wants to send you, where should we bring it?’ ” As part of that ruse, Mr. Himmelstein explained, investigators would walk up to the client’s other residence with a camera and videotape the client opening the door and accepting the case of wine. He said surveillance tapes now show up in about 20 percent of his cases.

Under the New York City rent rules, which cover half the 2.1 million rental apartments in the city, a tenant with a lease on a rent-regulated apartment must live in it at least half the year. He cannot sublet without the owner’s permission and cannot charge more than the regulated rent. When the primary tenant moves out or dies, only family members already living in the apartment for at least two years have a right to take over the apartment.

Owners are allowed to charge only a fraction of current market-rate rents. They can apply for deregulation only when an apartment’s rent reaches $2,000 a month and either the tenant moves out or the existing tenant’s household’s income tops $175,000 for two years in a row. But if a tenant leaves, the owner can raise the rent for the next tenant by roughly 20 percent, and pass on part of the cost of any improvements made between tenants.

Mr. Golodner himself lives in the rent-controlled apartment on the East Side of Manhattan where his father was born and died. He has worked as a bank teller, a meat cutter, a garage attendant and a paramedic, and was a police officer for 20 years. An occasional actor, he is working on a screenplay about a Jewish detective married to a Wiccan priestess.

“I’m not one of these pansy P.I.’s that sits behind a computer,” he said recently, mock-indignant. (He quickly volunteered that the line was lifted loosely from a private investigator in the movie “Intolerable Cruelty.”)

Two years ago, Mr. Golodner, 50, and Mr. Frankel, president of the board of his own condominium, formed Frankel Golodner & Associates. Half their business involves real-estate-related investigations, a niche Mr. Frankel, 61, discovered through his wife, who owns a real estate sales and management firm. But Frankel Golodner is full service — everything from matrimonial and nanny investigations to “executive protection,” and “corporate and event security,” including “explosive detection.”

The case that took Mr. Golodner out of New York City last week and up the steps of the stucco house was in a suburb that Mr. Golodner and Mr. Frankel asked remain unnamed as a condition of allowing a reporter to accompany Mr. Golodner. It was a typical “nonprime case” of a primary tenant suspected of illegally subletting her apartment and living elsewhere. Mr. Golodner said he figured he already had enough evidence to make his case against the woman, who he said was paying less than $1,500 a month for her Manhattan apartment.

He put his finger to the doorbell. High-pitched barking erupted inside — the kind that comes out of small dogs with ribbons in their hair. Mr. Golodner planned to tell the woman he was an insurance investigator looking into an accident that had occurred on the street some months before. With any luck, the woman would get chatty and volunteer something revealing — say, that she had lived there for years.

But she was tough. She opened the door just a crack. The camera nestled near Mr. Golodner’s solar plexus recorded nothing more than the crack in the door and an occasional glimpse of her hand. She seemed dubious about the accident story. When Mr. Golodner asked her casually how long she had lived in the house, she said she did not live there. She just stayed there with her boyfriend, she said.

Back in the car, Mr. Golodner said he had was ready to write up a final report for the client, even though the woman had not tipped her hand.

He recalled an earlier surveillance that had gone better. Another nonprime tenancy investigation, another Manhattan apartment, another woman living outside the city. But when Mr. Golodner had played the insurance investigator, he said, that woman took the bait.

“Oh no, three months ago?” he remembered her saying. “I saw the whole thing! I’m here all the time. They use this road as a raceway.” She had owned the house for 20 years, she volunteered; she had lived there for nine. And she had an office in Manhattan — which, Mr. Golodner said, turned out to be the apartment in question.

He chuckled.

“She wouldn’t shut up,” he said.

- Today’s Papers

Dead or Alive

By Daniel Politi

Posted Friday, Jan. 26, 2007, at 5:43 AM E.T.The Washington Post leads with news that the White House has authorized the U.S. military to kill or capture Iranians who are believed to be working with Iraqi militias. President Bush approved the program last fall as part of a larger effort to prevent the spread of Iranian influence across the region. The Los Angeles Times leads with the way in which Muqtada Sadr has been avoiding clashes with U.S. and Iraqi forces in the past few weeks. His followers are participating in the Iraqi government and some officials from his party are even meeting with U.S. officials. The Wall Street Journal tops its world-wide newsbox, and nobody else fronts, the latest from Lebanon, where the army has imposed a curfew in Beirut after at least three people were killed in clashes that began at a university between those loyal to the government and Hezbollah supporters. This raises concerns the Lebanese government can’t maintain any semblance of order, just as donors pledged $7.6 billion in aid to help the country rebuild.

The New York Times leads with a look at the extent to which the Bush administration has used secrecy while defending its domestic eavesdropping program. Some lawyers and judges are starting to push back and say that much of the secrecy is unnecessary and ultimately impedes lawsuits objecting to the program from moving forward. The first appellate argument in the lawsuits challenging the program will begin Wednesday. USA Today leads with data that show airline delays reached a record high last year. By several measures the delays seem to be higher than in 1999 and 2000, when they were so frequent that lawmakers threatened to take matters into their own hands. Planes were delayed a total of 22.1 million minutes last year.

For the past year, military officials have been detaining Iranian “agents” in Iraq and then releasing them after a few days, which the Bush administration felt didn’t go far enough. While some believe that hitting Iran hard in Iraq could dissuade the country from pursuing nuclear weapons, others believe that angering Iran would put more U.S. troops and citizens across the region at risk. There have been no known uses of the new authority, which excludes diplomats and civilians, but the military has apparently been pressured to use it more aggressively.

There are several interesting tidbits throughout the story, but the Post‘s Dafna Linzer leaves one of the best for the end. Two administration officials separately compared the Iranian government to the Nazis and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard to the “SS.” In addition, the officials used the term “terrorists” in talking about Guard members, which could make them targets in the “war on terror.”

Everyone seems to be skeptical as to why Sadr decided to lay off confrontation for now. Some U.S. officials fear this could all be part of a strategy to lay low while the pressure is on, but the change of tone is undeniable. One of the leaders in Sadr’s movements even endorsed President Bush’s new plan for Iraq.

Over in the Post‘s op-ed page, Gary Anderson does a little role-playing and imagines how a planner with Sadr’s Mahdi Army might react to Bush’s Iraq plan. Anderson lays out a few possible courses of action, but the one he says would serve “long-term interests” involves stopping any visible attacks, and instead targeting U.S. and Iraqi troops through snipers and bombs. This would keep “our fingerprints off such operations because the Sunnis will probably do this regardless of what we do.”

The Post fronts a dispatch from Baghdad that looks at the way many Iraqis see Iran’s influence in their country differently from U.S. officials, who talk only about military involvement. The two countries have a burgeoning commercial relationship, and many citizens of both countries feel a kinship to their neighbor. “The economic power between the two countries, it’s enormous,” said Iran’s ambassador to Iraq, who refers to Americans as “the others.” (TP assumes he didn’t mean to make a reference to Lost, even if some similarities are quite striking.)

The LAT and WP front, while everyone else reefers, the latest from the Scooter Libby trial. Yesterday, Vice President Cheney’s former spokeswoman testified she told Libby that Joe Wilson’s wife worked at the CIA days before he supposedly first learned of Valerie Plame’s identity from a reporter. The former spokeswoman also revealed Cheney was in charge of the effort to discredit Wilson. The Post puts the straight news story inside but fronts a Dana Milbank column that looks at the way in which yesterday’s testimony “pulled back the curtain on the White House’s PR techniques.”

Everybody mentions Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s announcement that the administration will ask for $10.6 billion in aid for Afghanistan, which is more than what the Post reported yesterday.

USAT fronts an interview with Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who confessed she misses Sandra Day O’Connor and the lack of another woman on the bench makes her feel “lonely.” Ginsburg recognized that “this is how it was for Sandra’s first 12 years” but noted “neither of us ever thought this would happen again. I didn’t realize how much I would miss her until she was gone.”

The NYT fronts, and the LAT goes inside, with a new study that reveals smokers with a specific brain injury can immediately stop puffing without getting any cravings. One man described how his body “forgot the urge to smoke.” Researches hope this will help them develop more efficient treatments for smokers who want to quit.

The LAT‘s Rosa Brooks* was convinced there was a secret message hidden in the State of the Union address, but she couldn’t figure it out. Then she decided to watch a Baby Einstein DVD, and it all became clear: “It was a cartoonish world of puppetry and sleight of hand, simplistic language, frequently repeated words, soothing imagery. And it meant nothing, nothing at all.”

Correction, Jan. 26: This article originally identified the writer of the Los Angeles Times column on Baby Einstein products and the State of the Union address as Ruth Marcus. The writer is Rosa Brooks. Return to the corrected sentence.

Daniel Politi writes “Today’s Papers” for Slate. He can be reached at todayspapers@slate.com.T- You Know You’re from N.J When…..

* You don’t think of citrus when people mention “The Oranges.”

* You’ve known the way to Seaside Heights since you were seven.

* You’ve eaten at a diner when you were stoned or drunk.

* Whenever you park, there’s a BMW within three spots of you.

* You’ve never pumped your own gas.

* You know where every “clip” shown in the Sopranos opening credits is.

* You can see the Manhattan skyline from some part of your town.

*You know that there are no “beaches” in New Jersey-there’s “The Shore,” and you know that the road to the shore is “The Parkway” not “The GardenState HighWay.”

* You know that a WaWa is a convience store

* You know what a “jug handle” is.- HOWARD HUNT, RIP

By William F. Buckley Jr.Fri Jan 26, 8:04 PM ET

My name has been linked to that of Howard Hunt, who died on Jan. 23, and I readily acknowledge that we were associates and close friends during the period (1951-52) when I worked for the Central Intelligence Agency in Mexico. Howard Hunt was my boss, and our friendship was such that soon after I quit the agency and returned to Connecticut, he and his wife advised me that they were joining the Catholic Church and asked if I would agree to serve as godfather to their two daughters, which assignment I gladly accepted, continuing in close touch with them.

Not so with their father. Howard Hunt, as has been widely recalled on his death, had a sensational career, including, in his 50s, 33 months in federal prison on charges of conspiracy, wiretapping and burglary. Some time after leaving prison, he asked me to recommend presidential clemency, which would have had the effect of clearing his name and reauthorizing him to vote. I told him I was reluctant to do this because in fact he had been involved in conspiracy, wiretapping and burglary, but I was careful to say that the reason he committed these crimes was that he thought himself engaging in public service by protecting the interests of President Richard Nixon.

He was terribly mistaken there, and in fact he was more responsible than any single other human being for bringing about Nixon’s resignation. Because it was Hunt who organized the Watergate break-in, seeking to advance the partisan cause of Nixon in l972. He had at the time already committed a crime by breaking into the offices of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, on a mission probably authorized by Nixon’s attorney general, John Mitchell.

Hunt came to see me, with one of my goddaughters, shortly after his devoted and alluring wife was killed in an airplane crash. He recounted the story of Watergate, giving me information not known to the press or even to the prosecution. Notwithstanding his plight, he wore a jaunty sports coat and, pipe in hand, reported that, soon after his arrest, “I said to myself, ‘Where’s the fix? Why didn’t they fix me up?’”

It was a genuinely appealing professional query. Howard Hunt had lived outside the law in the service first of his country, subsequently of President Nixon. The way things had worked for him, in Mexico, in Uruguay, in Japan, was the way he expected them to work now. You break the law in pursuit of your country’s interest as prescribed by your superior or by your cognitive intelligence of political reality. You get caught; and, if feasible, your government looks after you. If it’s bail that’s needed, it materializes. If it’s looking after your widow and children, that is done. If you are in Washington, D.C., having committed a crime on the authority of the attorney general or the president, why — Howard Hunt was saying — somebody … does something. And the charge against you for trespass, or burglary, or whatever, washes away.

But Hunt, the dramatist, didn’t understand that political realities at the highest level transcend the working realities of spy-life. He ended up in prison, a widower with some of his children on drugs, and bankrupt. I got him a fine volunteer lawyer.

I remember with sad amusement an earlier experience of Hunt’s with the law, this time involving his novels. Allen Dulles, then head of CIA, called him in one day and said, Howard, I know the rules are that this office has to clear all manuscripts by our agents. But you write so many, you’re wearing us out. So go ahead and publish your books without our clearance, but use a pseudonym.

Hunt handed me his latest book, “Catch Me in Zanzibar,” by Gordon Davis. I leafed through it and found printed on the last page, “You have just finished another novel by Howard Hunt.” I thought this hilarious. So did Howard. The reaction of Allen Dulles is not recorded.

We visited once or twice after his remarriage, when he was trying to re-establish himself as an author. But estrangement crept in. A year ago he asked me, through an intermediary, to write the introduction to his memoirs. I read them with great misgivings. There was material there that suggested transgressions of the highest order, including a hint that LBJ might have had a hand in the plot to assassinate President Kennedy. The manuscript was clearly ghostwritten.

I declined to write the introduction. But when the manuscript was resubmitted to me, with the loony grassy-knoll bits chiseled out, I said OK, but wrote an introduction restricted to describing our early friendship in Mexico. The book will be published (by John Wiley) in March.

And this former colleague here registers his old affection and admiration for a civil servant who ran into bad luck and lost his judgment, but who sought to serve his country and look after his children.